Chapter 1: Fall 1817

Twenty-Three Years Old

Simon skidded down a flight of stairs from the attic rooms and slid across the landing that overlooked a spacious square hall of wooden panels. Crashing into the newel post; he grabbed hold, steadied himself, and looked down at the mob of young men swarming into the center of the room.

Shouting would avail him nothing—they wouldn’t hear him over their cries of glee. They wouldn’t stop their “ritual” in any case. He turned away from the sight and veered into the long landing, heading for the front staircase.

The house was Truflian, built on a block structure—one great hall with a massive iron chandelier, one master staircase, one long landing edged on one side by an elaborately carved banister while three square rooms lined the other. His uncle lounged in the middle room, waiting to revel in the slander issuing from this latest bacchanal.

“Out of the way!” Simon shouted at the young men leaning over the banister railing, their eyes on the circling, stalking predators below.

Bets changed hands as Simon rushed past. He reached the grand staircase and half-fell down the first flight to sprawl on the landing; he pushed up immediately. The second flight hugged the house’s inside wall. Simon took the final steps two at a time and entered the fray.

He was tall, lean, and fit. He plowed through the outer circle of men, his eyes on the blond woman at their center.

A maid, a laundress, maybe a whore—though Simon’s uncle preferred to induce innocents to his parties’ entertainments. Simon caught sight of strong features: arched brows over blue-green eyes; a thin, straight nose; pronounced philtrum and long full lips.

A body lurched across Simon’s line of sight.

“Change her. Change her,” the men on the landing shouted, and the circling men chanted in response.

Simon pushed his nearest obstacle aside; the man—eyes wild, mouth open on a shout—looked about blankly. Simon was nearly invisible when he reached the woman and spat the potion in his mouth straight into her face.

She vanished completely.

The men on the landing roared—approval or disappointment, the sound was the same. Simon leaned forward, hands on knees, feeling the potion’s effects leave him, washed away along with the faint smell of Zingiber.

The hall quieted, shouts replaced by murmurs: “Where’d she go?” “Who did it?”

The circling men with their vials filled with potions rotated in small, abstracted circles, wolves denied prey. They would turn on each other soon but with less energy; some would begin to slink off to a tavern or a brothel for a bout of ordinary debauchery. Simon straightened and backed out of the horde. As the invisibility potion in his system faded, men began to see him, murmur his name.

“What potion did you use, Simon?” a fellow Academy student called from the landing.

Simon ignored him as well as other students’ glares and uncomplimentary mutters, their complaints because he had ruined the evening’s entertainment.

“When will she reappear?” another student called, curious, not petulant.

After you’re gone, Simon thought.

“Maybe never,” he said, and the observers on the landing broke into discussion groups, as if the whole event were merely another Academy lecture. Arms folded, Simon leaned against a wall, watched the group break up, and waited for his uncle’s summons.

“You ruined the evening’s program,” said Louis Ferrall, Simon’s uncle.

Louis Ferrall hunched in his four-poster on the second floor of the house, cracking nuts with his teeth. Simon watched the gray teeth chew, stained but firm. Their family descended from hearty stock; its members were distressingly long-lived.

Simon said, “Your last social gathering scandalized the king.”

Ferrall waved a hand. “Roger Moklin’s daughter. That may have been unwise.”

Roger Moklin’s daughter had accompanied an Academy student, that idiot Carl Foun, to one of Ferrall’s parties. Simon had been in the Academy lab that night, not in his own lab in the attic solarium. Reportedly, the girl had been transformed into a lizard, then threatened by stomping feet.

She wasn’t violated, the same reports claimed, as if preserving the girl’s virginal status excused terrorizing her. (The victim this evening would not have been so lucky.) Moklin’s daughter currently refused to leave her bedroom. Her father had complained strenuously to the king, who had instructed one of his ministers to inquire into the doings of the Academy and its students. If the inquiry deepened, Simon’s private experiments might come under scrutiny.

“Your guests could transform each other,” Simon said.

Ferrall grunted and licked his lips. “Not nearly as gratifying.”

Simon jerked his head—allowing for his uncle’s perspective without agreeing to it—and left the room. The man was Simon’s guardian. At age twenty-three, Simon no longer needed a guardian, but he did need his uncle’s money.

Simon’s parents died when he was thirteen, having fallen ill on a trip back from the family’s property in Lucorey when terrible storms stranded them in a noxious inn. After the funeral, Simon spent three years at his aunt’s, squiring her to dances and balls; he was tall for his age even then. When he was sixteen, she decided to spend her “waning years” in Ennance; his aunt had the strength of a Svetian ox, but she’d used up all Kingston’s social gossip, and off she went to fresher fields.

Simon stayed. He’d entered the Academy by then, and he petitioned to lodge with Louis Ferrall, the relative that even his lazy and luxury-loving aunt called “degenerate.” Ferrall lived in Kingston, and he had room, and he didn’t curb Simon’s excursions into Kingston’s slums.

Simon visited the slums to purchase hard-to-find herbs. If Ferrall was indifferent to Simon’s safety; he relished Simon’s course of study. When Simon cleared out the solarium and started collecting equipment and ingredients, Ferrall began inviting Academy students to his revelries.

“A bespelling brightens up any party,” he told Simon.

He started holding parties for Academy students exclusively—a chance for them to try out their latest experiments. Not all of the Academy heads approved, of course, at least not publically, but if Ferrall’s parties gave students a chance to refine their formulas, who was the Academy board to complain?

Simon didn’t kid himself: the board’s tolerance would last until fingers pointed in his uncle’s direction, then Simon’s. His uncle’s patronage was a mixed blessing, more a problem than a help. Like Simon’s aunt, Louis Ferrall fed on scandal, except that Louis demanded stories tinged with violence as well as salaciousness. He didn’t attend his sponsored revelries. He waited in his bedroom to collect the depraved details—like the shameful tale of an innocent girl turned into a lizard and nearly crushed by stomping, male feet.

A girl who merely vanished was not radical enough for his tastes.

Others disagreed.

The house didn’t currently have a butler—it wasn’t an easy place to staff—so Simon answered the door two days later. Duke Huvinney, a member of the Academy board, waited on the stoop with Professor Nerfause. Simon stepped back so they could move a few feet inside the door, no more.

“Simon,” the duke said heavily. “Everyone is talking, saying—you made a girl vanish?”

Simon shrugged. “A parlor trick.”

The men exchanged glances.

Professor Nerfause said, “The formula—”

The duke overrode him. “And where is she now?”

Simon quelled a surge of panic as he thrust his hands in his pockets. Tall and lean, he stood a head and more above the other men. He knew that his face bore the marks of Anglerey ancestry: high cheekbones, eyes shadowed by quizzical brows, a nearly hooked nose. Handsome. Sardonic. He let his features settle, knowing they conveyed nothing more than vague mockery.

He said, “She must have scurried off home.”

“Her brother—”

Again, the duke interrupted the professor: “She’s the sister of one of our tutors, a Mr. Tokington.”

Not a maid or a whore, yet not as troublesome a personage as Moklin’s daughter. A tutor could hardly bring pressure to bear on the king’s friends.

“A beauty,” the duke said seriously. “She was—maneuvered here.”

Forced, Simon grasped. Academy heads were given to euphemism, especially regarding student behavior.

“The Academy’s reputation needs mending,” the duke said as if Simon had spoken his thought aloud.

Simon said, “You can hardly expect me to monitor my uncle’s guests.”

“But you made her vanish,” Professor Nerfause broke in and pressed on; this time, he would not be overborne. “You may be permitted to maintain a lab away from the Academy, Mr. Ferrall, but you have an obligation to share your formulas.”

Simon allowed one eyebrow to rise. The Academy could not stop any citizen from acquiring beakers, mortars and pestles, even a cauldron. The ingredients for potions were harder to come by since many spells required special herbs. Still, slum magicians could cobble together and sell the simplest potions.

The Academy effected limited control: only Academy magicians could submit formulas for royal use; only Academy magicians could perform large-scale experiments. Simon could not be stopped from mixing potions—not legally, at least; the law did not recognize magic as an instrument of harmful behavior. But he could lose access to the Academy’s laboratory and, more importantly, its texts.

The professor said sternly, “Young man, you will hand over that formula.”

Simon shrugged. “I always intended to.”

Professor Nerfause grumbled into passivity.

Duke Huvinney said, “You are positive the girl left?”

That was not precisely what Simon had said; he nodded anyway. Neither man wanted to hear an equivocation nor did they did not ask to tour the house. They straightened their hats and coats and went down the path to a waiting coach. As the coach departed, Simon shut the outside door, took a deep breath, and strode to the center of the hall.

The woman had not reappeared. Most potions transformed their recipients for a few seconds, no more. Simon had perfected formulas where the effects lasted minutes at a time (a “true” transformation should last longer than the flicker of an eye). The vanishing spell was one of his strongest.

He had tried it on himself as an ointment and as a drink (the classic form of administration). He’d vanished for nearly ten minutes, during which time he’d slid into his uncle’s study and read his current will. When the man died, Simon would inherit his property. Of course, Ferrall might change his mind—if Simon ruined another of his parties, for instance.

Vanishing was the potion Simon spit into the woman’s face—to hide her, to keep her safe, long enough for the jackals to retreat. Except she should have reappeared by now. Perhaps she had when Simon was with his uncle: she’d reappeared and “scurried” away.

He neared the hall’s furthest wall and leaned against it, hands splayed along the paneling. Whispers. Shudders. The wood seemed to ripple. For an instant, Simon thought he felt an arm, smooth flesh, beneath his palms. He closed one hand over—nothing.

Groaning, he pressed his forehead against the wall’s wood panels. He must have imagined the arm. No formula was strong enough to—

Of course I imagined it. There was no other explanation.

Simon pulled on a long overcoat and went out in the crisp, fall day, coughing against a sudden intake of fresh air.

His uncle’s house sat amongst other two and three-storey mansions on the south side of Kingston’s Palisades district. Carriages rattled past, lords and ladies on their way to the Royal Palace at the top of Palisades’ hill. Simon circled the hill and crossed several roads before he reached a small park on its east side. Bushes lined a steep stone staircase which Simon took two steps at a time to a gate at the crest of the hill.

He was at the back of the Academy property, a series of stone buildings surrounding an oval drive. He headed beyond the furthest stone building to a series of ramshackle cottages. Tutors and mere instructors shared the cottages. Professors had apartments in the largest stone lodge that sat crossways to the Academy’s laboratory.

Simon slowed at the first cottage. The door was half-open; a tutor stood on the front stoop, straightening his wrinkled robe. “I need the mathematics chart,” the tutor called into the house. “You can pick it up from the classroom after.”

Not all tutors and instructors dealt with potions. The Academy claimed it wanted to diversify. Ever since Michaelis and Studdle failed to turn tin to gold, the Academy had felt the discomfort of placing all its nepotism eggs into one magical potions basket.

“Mr. Tokington?” Simon said.

The tutor glanced over his shoulder.

“Marcus Stevenson,” he said. “You are?”

Simon raised a brow. “Simon Ferrall.”

The tutor turned towards him fully. “You’re the Marquess of Anglerey.”

Simon raised both brows. “Marquess of Anglerey” was a dead title, linked to land in another kingdom. He had inherited the title at the death of his father, who had come into it after his two oldest brothers vanished into Lucorey’s wilds.

“Simon is enough,” he said. “Mr. Tokington?”

“Next door. He’s quite broken up about his sister.”

So she hasn’t returned. Simon didn’t let his consternation show. Watched by Stevenson, he crossed the weedy yard to the nearest cottage. The door opened rapidly at Simon’s knock, and he found himself face to face with a male version of the woman he had bespelled.

Almost. That woman had looked furious—ready to argue, to fight. This man looked sad, hangdog. He gazed pathetically at Simon. He motioned Simon morosely indoors. He slumped limply onto a worn ottoman. Simon stood over him and tried not to scowl.

He said, “Your sister hasn’t returned?”

“No,” the man said dejectedly. “Did you take her to Ferrall’s party?”

“No.”

Simon waited for expostulation—angry demands, forceful accusations—but the man only shrank back against the couch, hangdog expression at the fore.

Simon said finally, “I am Louis Ferrall’s nephew.”

“Oh. Do you have Hannah?”

His tone wasn’t even accusing. Simon stared at him, brows cocked—What kind of brother is this?—blanking his face when Tokington looked up with watery eyes.

Simon said, “I do not. Did—does your sister live on Academy grounds?”

“She was a governess for a family in Residence district. I persuaded her to give notice. It wasn’t right—having a sister in service. It didn’t look right. So she started working in the laundry here.”

“That was better?”

“I suppose not.”

“No,” Simon said emphatically. What brother in his right mind would keep a beauty like that in a place like this?

“She cooks for me.”

“How nice for you.”

Tokington rallied. “She disappeared from your house.”

“You should never have let the students take her,” Simon barked.

The man sighed heavily. “I didn’t know until later.”

“Then you should have gone and fetched her.” Fought for her if necessary.

“They would have brought her back—”

Tokington’s voice broke as he raised his head. Simon was done not scowling. He glowered, brows drawn. Tokington quailed.

“The dean was told,” Tokington said on a thin whine.

Simon didn’t bother to ask when the dean had been told—or by whom. He was willing to gamble Tokington hadn’t been the informer. Marcus Stevenson, more likely.

“They want your formulas,” Tokington told him.

“I know.”

“Oh, good.”

Simon glared at the bent head and weakly floating hands. Tokington would do nothing about his sister. He had already adopted the role of bereaved, victimized family member, the expression of martyr tacked permanently onto his handsome face. He wouldn’t even quit the Academy. Simon should be pleased, relieved. No fuss. No scandal.

He slammed the door on his way out of the cottage. From the nearby stoop, Marcus Stevenson watched, thumbs in his trouser belt.

“Where’s Professor Plysant this hour?” Simon said.

Stevenson flapped a hand towards a long, low building across the quad on the far side of the main house.

“In the laboratory. Morning lessons are ending. Potions, huh?”

Simon ignored the rising inflection (the man was clearly the type who loved a “good” debate) and tramped across the shriveled grass. A few students stood at the entrance to the laboratory, a stone building with a sloping roof. In an effort to mimic Ennancian universities—those bastions of research—the Academy had attempted to enhance the simple building with arched windows for light and an enclosed portico with a gabled roof. We too take experimentation seriously.

Simon ducked under the low entablature and entered the vestibule. Students dallied there, leaning against the wall outside the main room, conversing over open books. They eyed Simon and whispered to each other. A dark-haired student with rumpled hair and an insolent mouth pushed forward: Trevor Soulton, he had been at the party the night before.

“You kept Tokington’s sister for yourself, then?” he said to Simon.

“She found safer lodgings.”

“She was asking about you, you know. Before the party. What kind of potions you mix. Where you get your herbs. She wanted to go.”

“Did you force her?”

Soulton scoffed. “Not me. She must have convinced someone else to take her.”

The attendees would all say the same thing. Not out of fear of reprisals—Tokington was spineless; Duke Huvinney would never punish the sons of “good” families; Professor Nerfause only cared about Simon’s formulas. Prevarication was simply in their natures.

Simon continued into the building’s main room. The Academy’s laboratory wasn’t anything like his. Simon experimented with several formulas at once, using beakers, jars, and multiple bowls. The Academy considered such hands-on work plebian. It employed attendants who mixed the formulas at two long tables near the rear of each lab, using thick glass bowls (iron cauldrons were considered low-class). The front tables—stacked with books and unbound manuscripts—were used to work out the formulas on paper: toil for intellectuals.

Professor Plysant half-sat on his stool behind a slanted desk, idly marking sheets filled with measurements and herb names.

“That combination would produce nothing but gas,” he muttered before glancing up. “Ah, Mr. Ferrall. You’ve been causing quite the stir. There’s a reason we fuddy-duddys like to monitor students’ concoctions, you know. Individual experimentation is dangerous.”

“Supposedly. Not even Academy heads know how, ah, concoctions function.”

“And we never will if they aren’t monitored closely. Don’t ever give up on rationality, Mr. Ferrall.”

“And if a potion affects one person differently than another?”

“There will be a reason.”

“Such as?”

“Metaphysics, my dear man. The recesses of the soul may currently be unintelligible but we are no longer primitives bound by old superstitions—we will uncover the ties that bind together the higher orders of thought. As the soul’s colored unwinding—its excretions—manifest themselves—but of course, we must first be trained to recognize the unwindings—we will grasp the bonds between all living things. No more pills and broths—we will manipulate matter itself—prolong life—comprehend the dead—the unknowable known—”

Simon stopped listening. All conversations with potion theorists took the same path into gibberish. Potions were not like medicines, which could be duplicated and begat similar, if minor, alleviations in more than one person. Like medicines, potions used selective combinations of herbs and earth-based elements to create transitory bespellings: transmogrify, invisibility, flotation. But successful duplication was as rare as long-term effectiveness.

Simon had carried the invisibility potion in his mouth, and he was still here.

“How do we reverse the effects?” he interrupted the professor, who looked surprised (had he forgotten Simon was present?).

“Potions reverse themselves.”

“Not always.”

“Always. I assure you, my good sir—there is no such thing as permanence—potions carry within them the essence of all time and thought, reflections of the mortality, the mutability, of every man and woman—uncovering such truths is the duty of all great minds—”

A student came in with a query and Simon escaped Professor Plysant’s ramblings. Trevor Soulton still lingered in the quad. Simon strode past, stopped, turned, and gave the man a level look.

“I can do more than transform women into lizards,” he said.

He waited for the man to understand, to pale at the implicit threat.

“No more innocents at my uncle’s parties,” Simon added and walked on.

Maybe he could do more than lizards. Maybe he couldn’t. But he might as well make use of what people believed he could do to set a standard for what he might do.

Back home, Simon lay on a cot in the corner of the solarium. It was a long, narrow room with a pitch roof full of glass windows, some of the earliest in Kingston. Despite their grainy cracks and thick bubbles, they let in more light than the gloomy rooms below. Early morning shafts slid through the clearest portions, illuminating the room’s sturdy table. Tools covered the table, alongside Simon’s latest potions written on stained pieces of paper. The light touched a rolltop desk, its cover unable to close due to books stacked on its surface, then a cupboard of neatly stacked jars filled with blue, green, and brown mixtures.

Something was in the house. Simon heard whispers in the hall and on the landing, more and more often here in the solarium. The creaking boards seemed to breathe. The night before, Simon had sprinkled a generic cleansing spell on the floor, then sponged it down the walls. He lay down and waited, hoped.

At some point, without wishing to, he slept. A soft voice woke him:

“Caught. Trapped.”

“I’m sorry.”

Silence. Simon sighed, pressing his hands to his eyes.

“I could have stopped them. You didn’t have to intercede.” The voice was stronger, the tone more easily discerned. She was—irritated.

“Unlikely,” Simon said slowly.

“I have some skill of my own—at potions.”

“Is that why you quit your job as a governess? To learn about potions at the Academy?”

Simon dampened the exasperation in his own voice. He lay still as light from the windows chased shadows off the table and desk and piles of equipment. A thought struck him and he sat upright.

“Did you want to come here? You did ask about me.”

No answer. He lay down, staring blindly through glass ripples as the sky brightened from white-gray to white-blue. She couldn’t be such a fool.

The voice didn’t return. He got up when the sky was all blue and strolled across to the heap of books by his desk. Bradelyne wrote about retrieval—of memories specifically but any kind of retrieval might prove helpful. Poren discussed using spells to find lost objects. Simon weighed the top book in his hand.

“I wouldn’t bother with Poren,” the voice said. “He is all about seeing things through another’s eyes. Voyeur.”

The voice definitely rose from the wall. Simon leaned across the desk to press a hand against the splintered wood.

“I have to try something,” he said.

“You think I haven’t? I want to be part of this house? I can’t break free.”

“Are you hungry? Tried?”

“No.” The voice wavered before recovering its commonsensical tone. “And Bradelyne was barely a magician—within the meaning of the term. Metaphysical twaddle.”

She—Hannah—was nothing like her mawkish brother.

Simon said, “You should never have gone to work at the Academy.”

“I didn’t realize it was a training ground for rapists and idiots.” She sighed. “I should have used a disguise like those clever princesses in Anglerey operas.”

Simon felt himself smile, felt Hannah chuckle, a wave of motion through the floorboards.

He said, “Can you see me?”

A pause. “Sense you. Feel you. I know where and what things are. I can—move.”

The wall before him stretched. He saw the face of the woman in the hall, a sculpture of wood except for eyes of blue-green. She studied him, her expression wry, possibly annoyed before withdrawing; the wood regained its solidity.

Simon called, “Are you still there?”

No reply. Simon patted the wall and floor. He climbed onto the table and tapped the glass windows above his head. She’d sunk back into the house’s architecture. Yet he’d seen her: she was still herself and alive.

He set to work. Hannah returned when he was half-way through Bradelyne’s chapter on past-lives.

“Ridiculous,” she scoffed.

“Not if I can recreate his potion for past-life retrieval.”

“And I suddenly remember that once upon a time, I lived in splendor as a queen?”

Or remember how to be free.

“Why did you do this to me?” Her voice was curious, not angry.

“You know you were to be the party’s sideshow? Or prize?”

“I suppose I was unduly confident—”

“In your ability to protect yourself, yes.”

But Simon’s frustration at Tokington brother and sister had ebbed. Hannah was here. She was herself and could communicate. Restoration was possible.

She half-laughed. “So I missed one day of work.”

Simon stilled.

“Three days,” he said. “Three days of work.”

“Oh.” Her voice broke. “I had no idea.”

For the first time, Simon heard fear in the light, lilting voice.

“I will get you out,” he promised. “I will return you to the world.”

Chapter 2: Fall 1818

Twenty-Four Years Old

“You shouldn’t live here with your degenerate uncle.”

“You shouldn’t watch him at his private vices.”

“He corrupts this house.”

“Does he corrupt you?” Simon said, pausing in his perusal of Lohman’s Bodily Fluids.

“I’m too resilient.”

Simon allowed himself a smile.

“But you,” Hannah continued, “why do you reside alongside such disgusting behavior?”

“My uncle no longer holds parties.”

“Because I make his guests uneasy.”

Simon nodded. He’d heard the stories: “The floor shifts under your feet. The stairs and banisters actually move!” He’d encouraged them in quiet asides: “My uncle’s house has—things—in the walls.”

Students wanted jollification, not exposure to soiled, stinking corpses. Luckily, his uncle considered his guests’ desertion another good story. A temporary hiatus—they would return. He didn’t blame Simon. Yet.

“You remain,” Hannah pointed out.

“Because you do.” He’d said it before.

“You were entrenched in this cesspool before I arrived.”

She had a relentless moral center that overlooked her own safety. It wasn’t her choices she debated anyway.

She said, “Why didn’t you leave before—knowing what he was?”

“I’m good with potions.”

It was a sideways answer but one that she understood: the recklessness of the passionate mind that wanted more knowledge, more solutions, more control.

Except this time, she didn’t relent.

“He doesn’t care about potions.”

“He has money.”

And a house, which would someday be Simon’s.

“That’s a good enough reason to live with evil?”

“He isn’t—”

“He is,” she said sharply and was gone, whisking out of the desktop.

She moved through furniture as easily as walls, ceilings, and floors. The faintest ripples across surfaces denoted her arrivals and departures. He hated her absences more than her needling and watchful gaze.

He called, “Hannah,” even though he knew she wouldn’t answer until she was ready—able?—to return from her hideaway within the house. Give me time, he wanted to beg. Give me a chance to save you. But begging wouldn’t get him answers any faster.

“Does the house swallow you?” he asked her once.

“There are no rules,” she replied. “You created a false world for me to live in.”

“I saved you.”

Except he was no longer sure that he had. The Academy’s mixture of Simon’s vanishing formula—passed on to Professor Nerfause two months after Hannah’s disappearance—had not produce the same effects as Simon’s; students who drank the Academy’s brew rarely vanished for more than a minute, some for less.

“The formula’s effects could depend on the recipient,” Simon suggested when Professor Nerfause confronted him. “That person’s—soul.”

“Nonsense.” The man bridled. “Balderdash. Dated rubbish. I know what Plysant thinks: Magic is more art than science—blah, blah, blah. Spells can be replicated. Magic does not reside in the hands of the few and privileged.”

Nor in the hands of the many and querulous. Simon shrugged.

But he returned home and studied his original formula. There was one unmistakable difference between this and the one mixed at the Academy: on the night he’d made Hannah vanished, he’d carried the potion in his mouth.

Simon added his spit to his reappearance potion. The next time Hannah visited the solarium, he threw a cup of the stuff at the wall under which she moved. Nothing happened until—

Hannah rose from the wall, bas-relief emerging as a fully-formed statue. She arrived at an angle, so her head and shoulders appeared first, her hands breaking through a moment later. She glanced down at herself, laughed, and wiggled her fingers. Simon waited, breath held, sure it was working, that she was nearly free.

She snapped back into the wall, thighs, torso, head. Simon howled and hurled himself against the panel boards, covering them with the potion’s last dregs, which he pressed into cracks and crevices until his fingers bled.

He tried the same potion many times, adding more and more of his fluids, even his urine. More batches. More applications until the walls of the solarium were soaked inches through. He began to grab for Hannah, clutching her hands tight until she cried out in pain.

“Don’t let go,” she cried the last time.

And was gone.

“Why couldn’t you live at the Academy?”

Simon sighed and turned a page of Lohman’s chapter about the blood’s influence on mental states.

He said, “You’d be alone.”

“I think I could bear it.”

Simon couldn’t. Suppose he was the tether for her soul—suppose he left the house, and she sank so far into its foundations, she couldn’t speak or move? Invisible bones at the base of his uncle’s house.

“What day is it?”

She hadn’t asked in a long time. Simon felt himself cringe and focused on a list of purging herbs, face expressionless. The last time she’d asked, six months had past; she cried when Simon told her the date. Water streaked the glass panes even though they’d been no rain.

This time— “Fall,” he said.

She didn’t press him for the year.

The next morning, Simon went out before Hannah could ask one of her troubling questions. He wove around Palisades’ hill, passing the open fields that bordered the east side of the city. Veering to the west, one ended up in Docks district. Heading north, one ended up in Kingston’s slums.

“Trades district,” the ministers wanted to call that area.

“Slums” was a better term for a collection of winding cow-paths between stone hovels and wooden lodgings that leaned towards each other like vomiting men. The first—and only—slum resident to harass Simon had gotten acid in his face while Simon retreated with a cut hand and arm. Now the residents ignored Simon, and he ignored them as he stalked down the twisting lanes.

Reputable potion-makers operated mostly in Shops and sold mostly to the Academy. Although some had access to rare ingredients, they paid as high a price for the Royal Stamp of Approval as for the ingredients themselves. The royal family claimed the rarest herbs for their personal magicians.

The royal magicians were dabblers and poseurs, as decadent as Simon’s uncle with less imagination. Simon would rather go elsewhere than beg ingredients from the king and his cronies. He turned into a narrow alley between a gambling hell and a warehouse, kicking rats as he went. He rapped on the warehouse’s back door until it cracked open.

“You again.”

“Hello, Guy.”

“Anyone with you?”

“There never is.” Simon ducked through the door to stand in a gloomy passageway.

“I was thinking of her.”

Simon had the man by the throat before he thought. “What do you mean?”

“Rumors—people say someone haunts your house.”

“Not a rumor you’re going to pass on.”

“Of course not.”

Simon released Guy and pushed him forward into a side room stacked with bundled herbs beside jars of dried powders. Guy, tweed-thin with a bushel of tow-colored hair, peered up at Simon from a permanent slouch.

“Just making conversation,” he said.

“What do you have this week?”

“The Svetian borders have tightened up. I won’t be getting Luteola for awhile.”

“Useless anyway.”

“Good for loosening up the mind.”

“And turning it to mush. What else?”

“More Pinaster—that’s good for, you know, making the ladies happy.”

“I’m sure the royal family has masses of the stuff.”

Guy grinned.

Simon said, “What about herbs from Suvaginney?”

Without moving, Guy seemed to edge sideways. His eyes swiveled between Simon’s cheek and Simon’s shoulder.

“You never took them before.”

“I’m asking about them now.”

“Of course.” Guy tunneled through boxes and returned with three small jars. “Ordinary Vulgorisis,” he said, shaking the one filled with green leaves, “but better quality than most. This here is dried Urdica. And this—” Guy held out a jar of white pellets, eying it with a blend of disgust and awe. “Let’s just say, Suvaginney priests have to do something with the bones.”

“I’ll take all three.”

“Are you sure? Even—?” Guy shook the third jar.

“Yes,” Simon snapped.

“Power. Vigor. It’ll make your potions more effective. That’s what Suvaginney traders claim. I don’t give it away on account, by the way.”

“Half now. Half later.”

Guy struggled with the terms, face scrunched until his mouth met his nose, but he agreed. Naturally. Suvaginney ingredients were hard to come by; harder to sell. Even the royals refused to use them: Roesia did not do business with slave traders and primitive priests.

“They say the sacrifices are all criminals,” Guy said, pacifically accepting Simon’s packet of coins.

“Shut up.”

Simon couldn’t stop Suvaginneans from slitting criminals’ throats in their temples. The diplomats could do nothing about it either. Suvaginney was a continent away, reached by going overland through the Questing Kingdoms or, depending on the mood of Svetland’s regent, along its passable mountain corridor. Otherwise, sailors had to go far south and east to reach Suvaginney. Kingdoms like Veillur and Belget occasionally pled for assistance against Suvaginney from their neighbors—who did nothing.

Nobody ever did anything. The royal family debauched. His uncle watched others debase themselves. The Academy twittered about its potential effectiveness. Simon had something he could do, and he had to do it.

His sweat, his spit, his blood weren’t enough. A sacrificed victim’s should be.

Hannah was seemingly absent when Simon returned home. He started immediately, using the pestle and mortar to grind Vulgoris as he sprinkled in the Suvaginney bone pellets. He added Sativvuum, Eupatoria and a smidgeon of Urdica. Once the dried ingredients were a pile of fine granules, he poured in a thin stream of water to create a paste. It smelled of dried grass and then, tentatively at first, the sharpness of burning wood. Simon closed his eyes against the unexpected sting of smoke and breathed deep.

“What have you done? What is that?” Hannah, voice alarmed.

“It will free you.”

“Simon—”

“You know how close we have come.”

“I don’t recognize those white flecks—what did Guy convince you to buy?”

“We needed something more powerful.”

Simon added the final ingredient, the catalyst that every potion maker prepared during his first year of training: earth infused by incantations. Simon had his doubts about the incantations. A particular mixture of herbs, their combination of properties, seemed a more likely explanation for a potion’s results, but he was taking no chances this time. He sprinkled the earth atop the paste, worked it in with the pestle.

“Simon. I don’t think—”

She’d never sounded scared before. Righteously indignant, practical, commonsensical. Occasionally sad. She never spoke with this trembling uncertainty.

“You want to get free, don’t you?” he said, slamming down the pestle. “Go home? See your brother?” who refused to visit the house, to do anything overtly embarrassing or scandalous. “Aren’t you sick of my company?”

Usually, such a challenge would provoke a sarcastic reply: I would undoubtedly benefit from a more stimulating conversationalist.

“Hannah?”

“I want to escape—yes.” Her voice was as soft as sunlight, but Simon heard.

“Then trust me.” He picked up the mortar and a thick brush. “Where are you?”

“Here,” she said from the door.

Simon crossed the room. He sank the brush into the potion, lifted the clogged bristles, and began to sweep them up and down the panels.

“Oh!” She gave a cry of pain or surprise, maybe exaltation.

Simon didn’t stop. She was forming, rising towards him out of the wood, low to high relief, two- to three-dimensions. He knew the look of her: a slender figure with high, firm breasts, a head shorter than Simon. Her simple, flowered frock was too short for a lady, showing off shapely legs. There was the knee, the calf.

Emerging bare arms began to lose their wooden color and texture, growing creamy and supple. Her neck was entirely free; she rolled her head. Long, ash hair framed a face that had caught the attention of the Academy population a year earlier. Simon discerned the straight nose and wide mouth, tight in this moment though good-humored creases lurked at the corners. Blue-green eyes under faintly winged brows met Simon’s.

The full-lipped mouth parted as if to greet him. A thin, high wail issued from it instead. Hannah’s head arced, eyes closing. Arms and legs spasmed. Simon continued to apply the potion, directly now, splattering the dark, wet material across Hannah’s cheeks and neck and hands—throwing globs of it onto her surfacing feet.

She was nearly free of the door. Simon was pressing the brush into the mortar to pick up the layer of paste along its bottom when Hannah jerked back as if pulled by multiple strings. For a moment, she was flush against the door, then in the door, a recessed carving. It stood, her form etched across its surface, then collapsed in a flurry of chips and sawdust.

Simon shouted and dashed forward, tripping on the debris. He stood at the top of the stairs leading to the lower floors. He called. He turned in circles, nearly tumbling backward into the stairs’ shadowy descent.

Hannah was nowhere to be seen.

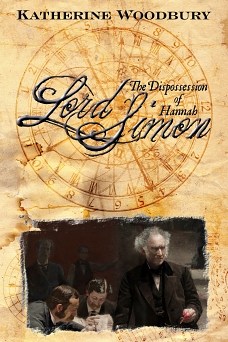

Read the rest

Paperback

Kindle

Smashwords

Apple Books

Google Play

Nook

Kobo

No comments:

Post a Comment