December 07, 2005

All in the anime harem family

The thought occurred to me while I was watching the fascinating anime series Elfen Lied (from the German elfenlied, "elf's song," the third syllable a long /i/), the opening ten minutes of which may be some of the blood-spatteringest ever. Some two dozen people get decapitated, dismembered and eviscerated in a row, sort of an extended version of the killer rabbit scene in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, except these guys seriously don't know when to "Run away!"

The thought occurred to me while I was watching the fascinating anime series Elfen Lied (from the German elfenlied, "elf's song," the third syllable a long /i/), the opening ten minutes of which may be some of the blood-spatteringest ever. Some two dozen people get decapitated, dismembered and eviscerated in a row, sort of an extended version of the killer rabbit scene in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, except these guys seriously don't know when to "Run away!"The killer rabbit in this case is Lucy, a mutant superhuman with a murderous chip on her shoulder and a case of amnesia that turned her into schizoid psycho killer. A cute psycho killer, naturally. She is rescued by Kouta and Yuka, completely unaware of the ticking time bomb they've just picked up, and taken to Kouta's family estate, where he had been living alone. They also take in Mayu, another basket case (human). A little while later, Nana, Lucy's sort of kinder, gentler version shows up.

That's when it struck me: this has got to be the weirdest-ever contribution to the harem genre. The harem genre is unique to Japanese Y/A shounen (boy's) fiction. The way it works is, usually through some contrived, sit-com circumstances, one guy ends up living cheek-by-jowl with a half-dozen or more tremendously attractive girls. Sort of like the crazy old lady on the corner with the cats, except that the protagonist collects girls; or rather, they end up collecting him.

We're definitely in Madonna/Whore territory here. The female protagonists are as chaste as nuns, rationing their sexuality with the discipline of an Orwellian regime (though sexually titillating characters or situations will be tossed in as often wildly inappropriate "comic relief"). And the guy is generally stuck at the emotional age of thirteen and is passive as a stump.

Of course, in the hentai (whore) versions, the lion is kept quite busy servicing the pride (and/or visa-versa). But hentai's bark far exceeds its market bite and strikes me as more a fantastical exercise in overcompensation precisely arising out of pervasiveness of its mainstream counterpart. For in the popular mainstream versions (again, published initially for the Y/A shounen market), glaciers outpace character development and no relationship is EVER consummated.

In the corresponding shoujo (girl's) genres, to compare, the relationships do generally go someplace. Slowly, to be sure, but ground is covered. Lessons are learned. Steps are taken. Take sex, for example. In His and Her Circumstances, Yukino and Arima eventually sleep together. As do Karin and Kiriya in the shoujo manga Kare First Love. And in the stupendously popular shoujo manga, Nana, the two primary boyfriend/girlfriend relationships are consummated by the end of volume 1.

It never happens in the harem. In an early episode of Ai Yori Aoshi, Kaoru and Aoi do sleep together, but they only sleep. And that's the last time that happens. The next thing you know, he's living in a girl's dorm (and not getting any there, either). In Tenchi Muyo, Tenchi gets hits on repeatedly by his female alien houseguests but hasn't yet gotten to first base on this or any other planet so far as I can tell. Nor does he seem to be trying very hard.

And who can blame him, when some alien warship is always inconveniently invading Earth and landing in the living room? Vandread, an equally broad comedic space opera series, does make some clever puns whenever the one guy-piloted mecha fighter "joins up" with one of the gal-piloted mecha, but don't count on any of the relationships moving beyond the metaphor. To start with, they're too busy battling the bad guys (and you apparently don't need men to get pregnant, anyway).

Abstinence as a plot ploy achieves a state of farcical excess in Maburaho (and goes over the top in the execrable Mouse), with our hero rejecting the explicit advances of three of his coed classmates. He provides no moral grounds for doing so, except, I suppose, he's offended that they don't want him for his mind. Okay, one of them does want him dead as well as bedded (it's complicated), but the other two are eager and willing, and one of them is all ready to move in.

What makes this even more bothersome is that a good reason other than an endemic case of cooties would make the farce funnier. Just as in Ai Yori Aoshi, Kaoru and Aoi having the kind of relationship you would expect of reticent nineteen-year-olds, not twelve-year-olds, would make for better story lines, even without losing the slapstick material. By the end of the series, Hand Maid May similarly begins to gnaw at you. What in the world doesn't Kazuya see in Kasumi? She's smart, funny, competent, cute. And she's human. Oh, yeah. Human.

And speaking of cooties, Masakuza Katsura, who penned the unexpectedly sweet Video Girl Ai, also concocted the often just annoying DNA2, whose male protagonist is literally (and I am using "literally" literally) allergic to girls. The exact same plot device is again deployed in Mario Kaneda's Girls Bravo (the kid actually breaks out in hives).

But the worst of the lot—because it pretends to some realism while going on and on (and on)—is Love Hina. Keitarou is a ronin (an unmatriculated high school graduate) trying to get into Tokyo University. When his grandmother retires from running a girl's dorm, she ropes him into being the live-in manager. Ostensibly, Keitarou will fall in love with one of the borders whom he (wrongly) believes once promised to attend Tokyo U with him, but frankly, it's guys like him that arranged marriages are for.

Brigham Young University (speaking here from personal experience), rated by the Princeton Review as America's "most stone-cold sober campus," is hotter than the Las Vegas strip compared to this bunch. Keitarou and his sort-of-significant-others are so feckless and emotionally inept and just dumb that I can't watch it without wishing that a psycho killer would move in and do something really decisive with a big knife.

The protagonist in the harem genre is often a student living alone or at a boarding school (Mahoromatic, Maburaho, Please Twins, Happy Lesson), a ronin studying for his college entrance exams (Love Hina) or a college student (Ai Yori Aoshi, Oh My Goddess, Hand Maid May, Elfen Lied). Between the regimented hell of high school finals and the regimented hell of corporate life is the one period of life during which a Japanese man pretty much has permission to do nothing the best he knows how.

As he will rarely consider marriage until he has "settled down" with a degree and a job, introducing sex, commitment and marriage at this point would only spoil the fantasy with too much hard reality. (And that "settling down" can take a while. Median age at first marriage in Japan is 30 for men and 28 for women; in the U.S. it is 27 and 25, respectively.)

Many a male high school student must dream of reaching this safe stage of life and staying there forever, like all those American Graffiti boomers who can't get over high school. The irony is that exactly what these Peter Pans are trying to avoid is precisely the point of the shoujo genre. Kinko Ito, professor of sociology at the University of Arkansas, points out that while shoujo stories primarily revolve around a "small number of characters . . . in intimate relationships," those found in

men's weekly comic magazines entail many characters [hence, the harem] and elaborate story lines. This is very similar to the games that boys and girls play. Boys engage in group games with rules, structures, and hierarchy while girls tend to form a group of a few and share intimacy.

One direction to take here is Rene Girard's theory of mimetic desire as applied to the psychological dynamics of the harem. Illustrating the proposition, Philippe Cottet observes that (paraphrasing his rough English translation),

the infatuated girl praising the qualities of her boyfriend to her girlfriends asserts the superiority of her happiness in order to confirm her own desires. Her friends, envious of this happiness, desire the aforementioned friend in turn. Their desire reinforces in the girl the certainty that he is the "one." The object is not anymore the undoubtedly rather banal boyfriend of Miss X, but an illusion arising from rival desires. Outside of this rivalry, at a place of observation not contaminated by this illusion, all will ask the question: What in the world do they all see in him?

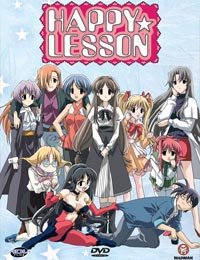

That question is too often the only one remaining on the viewer's mind after the video ends. If the five supposedly grown women in Happy Lesson so badly want a child to fawn over, why not do it the old-fashioned way? Perhaps because every Peter Pan has his Wendy.

Still, from the obvious-on-its-face perspective, Cattet's reading of Girard may be spot on: the harem simply represents the universal male desire to be desired by attractive women, and the female desire to desire something that will reciprocate that desire, however juvenile the form of reciprocation. But I believe there's another fantasy at work here, one more deeply rooted in the psyche, one more substantively responsible for the popularity of this specific genre: the harem as family.

According to this formulation, the male protagonist is less a potential lover than a stand-in father/brother/son. Each of the women in the harem, in turn, represents one facet of the ideal mother/wife/sibling figure, from tomboy to sex kitten to kid sister to parent and traditional homemaker. There's usually a lay Shinto priestess or sword-wielding Zen master in there, too. And if the plot mechanics posit that if a pair within the harem pair off—the principal male and female characters—then they become the de facto parents (though with curfews and separate rooms).

In fact, the shounen/harem genre does much better dramatically when the principals start off somewhat committed to each other, making them proxy parents by design. Oh My Goddess (Belldandy and Keiichi) and Ai Yori Aoshi (Kaoru and Aoi) begin with the girl making the first move and the two of them living together—only living—before the houseguests/siblings move in. In the former case, Keiichi's sister and Bellandy's sisters; in the latter case, Kaoru's female college classmates.

But none of his male college classmates. The male lead fills all of the designated male roles.

Sometimes, though, there is no metaphor to decode. According to the premise of Happy Lesson, five twenty-somethings decided to adopt an orphaned boy (Chitose). However, Happy Lesson isn't the flipside version of Three Men and a Baby. It's "Five Women and a Teenaged Boy." This immediately suggests an Oedipal subtext, but the explicit image of mother-as-sex object is one projected towards the viewer and blithely ignored by the actors, though it can be raised as an external threat.

Sometimes, though, there is no metaphor to decode. According to the premise of Happy Lesson, five twenty-somethings decided to adopt an orphaned boy (Chitose). However, Happy Lesson isn't the flipside version of Three Men and a Baby. It's "Five Women and a Teenaged Boy." This immediately suggests an Oedipal subtext, but the explicit image of mother-as-sex object is one projected towards the viewer and blithely ignored by the actors, though it can be raised as an external threat.One episode of Happy Lesson has a seedy real estate agent trying to blackmail Chitose with photographs that could be easily interpreted by the casual onlooker in very much the wrong light. This is seen as a direct challenge to the family structure (rather than an articulation of the patently obvious), and is fought with typical sit-com strategies and resolved with typical sit-com moralizing, again, emphasizing the primacy of the family unit above all other considerations, despite its artificial origins.

This kind of material plays on real-world taboos while staying on the side of angels. The tabloid press in Japan revels in stories of illicit teacher/students trysts as well as Oedipal (in Japanese, mazakon, or "mother complex") relationships getting decidedly out of hand, all reported with the expected hand-wringing salaciousness. On a base level, Happy Lesson is one long exercise in nudge-nudge, wink-wink.

In Hanaukyo Maid Team, the nudging and winking is done with a two-by-four to the back of the head. After his mother dies, Taro inherits his grandfather's mansion and its all-female staff. So predictable is this setup that all the characters could be cut and pasted from Love Hina or Happy Lesson or Oh My Goddess, with slight adjustments to hair color. There's Mariel, the "maid in chief," who becomes the mazakon figure, a clutch of spunky sister figures, the stern authority figure, and a trio of sexually precocious "personal assistants."

As for those latter three, this time around the whole cooties thing does make sense, as Taro appears to be about the age of eleven. But it also makes the running attempted statutory rape gag less than amusing. There certainly is no accounting for what some people think is funny. Or what constitutes "children's programming" in Japan. Or if it's not for children, what in the world the adults are reading into it.

But as noted above, the odds of sexual desire being acted upon within the harem are exactly zero. The taboo is purified and expunged, the impulse transformed into an expression of amae. Amae is the root of amaekko, or "spoiled child." As a verb, it can be used transitively, meaning "to mother" or "to indulge," and also intransitively, meaning to be put in the position of being pampered or taken care of. It describes a mutually dependent relationship (with the male making the token effort of rejecting it).

The expression of amae within the genre is the tried and true recipe for family formation. In Hanaukyo Maid Team, the family unit is first defined by Mariel, as substitute mother, making the newly-orphaned Taro her amae object. Later, a vulnerable "younger sister" (Cynthia) is introduced, becoming his amae object. Then the stern, father-figure (Konoe) warms to Taro and he comes to her rescue in turn. The family grows as each member demonstrates its willingness to take care of and be taken care of.

The rule-proving exception is Fruits Basket. I call it an exception because it follows the harem formula but comes out of the shoujo (girl's) category. Orphan Touru is taken in by the Souma family, three male cousins who share an ancient Chinese curse—they change into creatures of the Chinese zodiac when hugged by a non-clan member of the opposite sex. So right from the start, the asexual nature of the household is ensured.

Although a tenuous romantic relationship does eventually grow between Touru and Yuuki, her primary role is that of sister and mother figure, who starts out being rescued (the amae object) and ends up rescuing them (the amae giver). Despite its Pollyannaish gloss, Fruits Basket (and this is true of the shoujo genre in general) is far more sophisticated about the intricacies of human relationships than most shounen products. Touru eventually exerts a maternal influence on the entire clan, putting her into conflict with its tyrannical (and emotionally repressed) male head.

As with Fruits Basket, this theme of the "discovered" or "invented" family, often centering around the orphan/missing parent motif, turns up in genres far removed from the shounen "harem."

A case in point is My Dear Marie, in which Frankenstein-wannabee Hiroshi invents an sentient, anatomically-correct android girl to be his . . . sister. At the other end of the age spectrum, junior high student Nana of Nana 7 of 7 isn't an orphan. Her parents are working overseas, another common plot device. She is living with her mad scientist grandfather when she accidently clones seven copies of herself, each with a unique personality. In other words, she's now got seven sisters.

In Figure 17, another pre-teen shoujo title, Tsubasa moves with her father to Hokkaido after her mother dies. There she stumbles onto a secret escaped alien monster recovery operation (again, it's complicated). In the process, she accidentally "actives" Hikaru, a super-duper monster killer whose avatar looks just like her. Advertised as a girl-oriented superhero series (e.g., Sailor Moon), the show spends far more time chronicling the normal sibling relationship between Tsubasa and Hikaru.

Kaoru in the aforementioned Ai Yori Aoshi is an orphan. Suguru in Mahoromatic is an orphan, as are Toru in Hanaukyo Maid Team, Chitose in Happy Lesson and Mike in Please Twins. Just like Chitose, Mike (he's half-Caucasian) has returned to the town of his birth and scraped together enough money to rent the house he grew up in. One day, two girls show up on his doorstep, each claiming to be his long-lost twin sister. Of course, both end up moving in. Mike becomes father, brother and potential lover to the girl who isn't his sister, a possibility perpetually postponed.

In the opening episodes of Tenchi Muyo, Tenchi is living alone with his grandfather when the crew of alien girls move in. His mother died when he was young and his ne're-do-well father absconded. In Read or Die (the television series), Michelle, Maggie and Anita (all orphans) live together as sisters. It's several episodes before we realize they are not even related. When Anita rebels against the pretense, Yomiko tells her, "You have the kind of relationship I would want if I had sisters."

Elfen Lied takes this formula to the extreme. The mutation that gives Lucy and Nana their superhuman powers also programs them to kill their parents. So they're all orphans (except for the horrifically empowered Mariko, whose father is one of the mad scientists).

In particular, Elfen Lied and Mahoromatic share several highly informative similarities (besides the gratuitous nudity). Mahoromatic is the more conventional of the two series (according to manga/anime standards), and more comic than dramatic. Mahoro is a combat android, essentially a killing machine created to fight a secret alien invasion of the Earth. The initial battle won, and with only a year left on her life span clock, she retires and moves in with Suguru, the son of the man who had been her commanding officer, ostensibly as his live-in maid.

Mahoro and Suguru then proceed to collect a stable of other characters around them, filling out the familial and sibling roles (see accompanying graphic).

Mahoro and Suguru then proceed to collect a stable of other characters around them, filling out the familial and sibling roles (see accompanying graphic).Both stories play out against the background of (yet another) fiendishly complicated conspiracy to take over the world. Both Mahoro and Lucy are burdened with guilt arising out of violence they inflicted on the protagonist's family, that left Suguru and Kouta orphans. The important difference in their behavior is that Mahoro's intact conscience now leads her to compensate with an motherliness towards Suguru (when she's not dating him), though the relationship ultimately resolves with Mahoro playing a purely parental role.

Lucy's conscience, in contrast, has become binary. She is either childish and innocent (her mere presence literally disarming of her sister mutants), or knowledgeable and ruthless, a doll-faced, pitiless Shiva. She first discovers her powers when, as a elementary school child, she slaughters a gang of kids teasing her. She then goes on a killing spree, with her reductive reasoning leading her to simply walk randomly into a house, kill its occupants, and live there until she is discovered or runs out of food.

When Kouta takes her in, she has reverted to her childish mode, thus making her the object of amae. Kouta's only romantic attachment is to his cousin, Yuka, and so, as the formula dictates, he takes on a strong, paternalistic role. The next addition to the family is Mayu, fleeing child abuse, so also an amae object. Nana, Yuka's genetic kin, who still possesses a conscience, which makes her vulnerable to Lucy's rages, has been abandoned by her mad scientist guardian who, a la Snow White and the Woodsman, was supposed to kill her.

Writer Lynn Okamoto and director Takawo Yoshioka have taken a well-worn genre and sculpted from it a very Grimm tale (as well as a clever retelling of the Prodigal Son), spinning the wheel of fate between the destruction and creation of the world as symbolized in the annihilation and karmic rebirth of the family. When Mariko, the last and unredeemable mutant, is suicidally destroyed by her real father, the only human she spares after slaughtering all parental pretenders, time again moves forward and the family is reborn.

Indeed, Mayu confirms the thesis when she plainly tells Yuka, "You are the mother and Kouta is the father of this house."

It has become a tale for our time. Dystopians once imagined a Brave New World of globally-rationed reproduction. Remember Paul Ehrlich? Soylent Green? I predict that future historians will note that such schemes were attempted over the course of a quarter-center in China, but that China soon started frantically scrambling in the opposite direction as socio-economic factors made coercion mute and the birth rate plunged below replacement.

Instead, we are facing a future unimaginable only decades ago, one devoid of brothers, sisters, cousins, aunts and uncles. With a fertility rate of only 1.29, out of every five Japanese families with at least one child, only one will have two children. The more rare a thing is, the more prized, and the more impossible it becomes to recover. The harem genre echoes a desire for the large, "traditional," extended family that may soon exist only in fairy tales.

Labels: anime, deep thoughts, demographics, sex, shinto, social studies

Comments