September 29, 2005

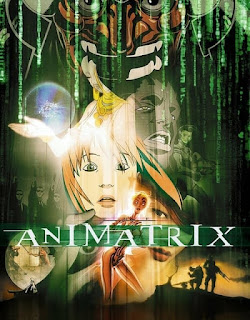

The Animatrix

The first Matrix movie worked by ignoring both the cause and implications of this egregious violation of the law of entropy. Unfortunately, when digging resumed, the holes only got deeper. The Animatrix was created as a bridge between the second and third Matrix movies (while the machines were swapping out drill bits, I suppose). It is a good example of how a bad premise can suck the life out of all that springs forth from it.

But it also proves what creative people can do when they are allowed to forget about said dumb premise and get on with telling good stories with interesting characters, not waxing on and off philosophical.

In actuality, the "bridging" material is found only in the first of the eight mostly self-contained vignettes. Rendered digitally by the Final Fantasy team, it is often indistinguishable from live action, and consists solely of telling us that the bad guys are on the way. Though tasked with that simple job, it manages to be more clever and cohesive that the sequels it segues to.

It takes real fortitude to wade through the second and longest of the vignettes (told in two parts, no less), in which the Matrix backstory is painstakingly explicated. A bad premise is bad enough. A bad premise painstakingly explicated is God awful, so intellectually empty it must be propped up by a top-ten list of hackneyed SF tropes that went stale back in the 1960s.

Made worse by attempts to weigh down the material with excessively literal cinematic references to every Important Historical Human Event in the past century. The result is a primer on "Why We All Suck" (in the future, everyone will apparently be channeling the ghosts of Noam Chomsky and Ramsey Clark, reason enough to pray for an apocalypse). It looks "profound," but it is a patina of profundity papering over miles of pretentious, self-loathing cliche.

It's sad to see such good animation sacrificed to such superficial material. Though if you forget about The Matrix, what we are actually left with is the backstory to The Terminator. It's The Terminatrix, really. It's less depressing if you think of it that way.

Thankfully, once we are whisked back into the world of The Matrix, not asked how it got that way or how it will end (eschatology should not be left to amateurs), things improve remarkably. An ad hoc group of Japanese animators were each given a theme and a boatload of Hollywood money to work with. The final product is as animated Twilight Zone, an ecclectic and often brilliant potpourri of stories and styles.

True talent will out, and here it does. But a potpourri it is, a succession of nibbles that whet the appetite but never truly satisfy. You wish The Brothers had spared us the Matrix sequels and instead done full justice to just one of these ideas by one of these directors.

In the end, though, what really recommends The Animatrix is the bonus material. You have to endure the requisite kissing-up, but the commentary is worth it. The mini-documentary about manga and anime is the most concise examination I've seen of the subject. Next time some non-otaku wants to know what the big deal is, pop in The Animatrix and watch this part first.

And then, instead of another one of those other Matrix movies, watch an anime series by one of the featured directors (Cowboy Bebop, to provide one example). It'll be time much better spent.

Labels: anime reviews, science fiction

September 25, 2005

Prologue 3 (A Thousand Leagues of Wind)

The Rishi (里祠) is the sacred building in the center of every city where the riboku tree (里木) is enshrined. See chapter 53 of Shadow of the Moon.

龍旗 [りゅうき] Ryuuki (dragon flag), flag flown when a king is chosen by the kirin.

王旗 [おうき] Ouki (imperial standard), flag flown when a king accends the throne.

赤子 [せきし] Sekishi, lit. the "Red Child," the era name of the Royal Kei Youko.

雲海 [うんかい] Sea of Clouds

瑞雲 [ずいうん] Zui-un, lit. auspicious clouds"

蘭玉 [らんぎょく] Rangyoku

桂桂 [けいけい] Keikei

蓬山 [ほうざん] Mt. Hou, not to be confused with the Kingdom of Hou (芳)

華山 [かざん] Mt. Ka

碧霞玄君玉葉 [へきかげんくんぎょくよう] Hekika Genkun Gyokuyou

西王母 [せいおうぼ] Seioubo

舒覚 [じょかく] Jokaku

崇山 [すうさん] Mt. Suu

天帝 [てんてい] Tentei

瑛州 [えいしゅう] Ei Province

里祠 [りし] Rishi

尭天 [ぎょうてん] Gyouten

凌雲 [りょううん] Ryou'un

金波宮 [きんぱきゅう] Kinpa Palace

玄武 [げんぶ] Genbu

冢宰 [ちょうさい] Chousai

懐達 [かいたつ] nostalgia (懐) for King Tatsu (達)

Labels: 12 kingdoms, wind

Prologue 2 (A Thousand Leagues of Wind)

The nengou system, called kokureki (国歴) in the novel, resets to year 1 upon the accession of a new emperor. In the past, technically, emperors could chose a new nengou whenever the fancy struck them, which is why you can have a nengou of "Eiwa 6" when the king has been ruling for 30 years.

The Japanese emperor is never addressed by name (first or last) as are European royalty (e.g. Prince Charles). It is also considered rude in general for a subordinate to refer to someone of higher social stature by their actual name. Title is preferred. Even within families, a younger child will refer to an older sibling as aniki (lit. "older brother") or aneki (lit. older sister) rather than by name or even the pronoun "you" (the worse insults in Japanese are derivations of "you").

"loaf of bread": I couldn't resist the Jean Valjean reference; originally 「一個の餅」 or block of mochi, pressed and dried rice that has the approximate consistency and appearance of hard paraffin. Pre-refrigeration, it was the only way to store cooked rice.

芳 [ほう] Hou (kingdom name)

峯王仲韃 [ほうおうちゅうたつ] lit. "Summit King" Chuutatsu of Hou

峯麟登霞 Hourin Touka (kirin of Hou)

孫 [そん] Son

建 [けん] Ken

永和 [えいわ] Eiwa

鷹隼 [ようしゅん] (arch) lit. "hawk and falcon," Youshun

蒲蘇 [ほそ] Hoso

祥瓊 [しょうけい] Shoukei

佳花 [かか] Kaka

恵侯 [けいこう] Marquis of Kei, Kingdom of Hou (Kei Province Lord), not to be confused with the Kingdom of Kei (慶)

月渓 [げっけい] Gekkei

梧桐 [ごとう] Godou

白稚 [はくち] Hakuchi

二声 [にせい] Ni ("two") + sei "voice")

Labels: 12 kingdoms, wind

September 21, 2005

Steamboy

But the story itself is pretty one-dimensional. It brings to mind those hokey old James Bond flicks in which some Dr. Evil is out to conquer the world with his latest contraption that breaks all the laws of thermodynamics. In this case, a supercharged, super-compact steam boiler that will revolutionize the mechanical world. There's even a pipe organ. No mad scientist should be without one.

As you might guess, Steamboy is about a boy (voiced in English by Anna Paquin) who's around steam a lot. Like I said, not a lot of nuance. His father (Alfred Molina) is at loggerheads with his grandfather (Patrick Stewart) over the ethical implications of the invention, and their little disagreement ends up taking out a good portion of downtown London. Think of it as a steam-powered version of Godzilla, a roller coaster ride that ends with a gigantic, flying train wreck.

The ostensible bad guys are a bunch of arms-dealing Americans funded by the (Scarlett) O'Hara Foundation (grin). The mannered but only slightly less corrupt Brits are led by Robert Stephenson (drawn a lot like Roger Moore), obviously a nod to the 19th century inventor, George Stephenson, the "Father of the British Steam Railways." And, of course, an annoyingly bratty girl (the aforementioned Scarlett), who is unexpectedly entertaining in all her brattiness.

In the original Japanese, at least. In the English version, she's more annoying than entertaining. (Japanese voice actresses have a gift for amusing annoyance that's all their own.) Otherwise, the dub is one the best I've heard.

Director Katsuhiro Otomo, who gained fame for his apocalyptic cyberpunk anime, Akira, has this time around produced pure period eye candy with a world so wonderfully realized that you want to throw every other Victorian character you know into the mix. The wealth of mechanical detail as well—the whirring, clanking, hissing, and grinding of gears—will keep any kid with a hint of the nerd in him on the edge of his seat just to see what gizmo they'll think up next.

Plenty of room was left at the end for a sequel, and having got the setting down pat, maybe they'll come up with a story with a bit more there there next time. In fact, the what-happens-next narrative during the credit scroll is the most complex of the movie, so be sure to watch all the way to the end. It's so good that in the DVD extras, you can watch it again without the scrolling credits getting in the way.

Labels: anime reviews, personal favs

September 18, 2005

Prologue 1 (A Thousand Leagues of Wind)

The context places this chapter in the early Meiji, or latter half of the 19th century.

The context places this chapter in the early Meiji, or latter half of the 19th century.Traditionally in China and Japan, a child was counted one year old at birth, and then a year older every lunar New Year. So, technically, a child born in December could be 2 years old a month later.

In Tonari no Totoro, Satsuki falls into Totoro's burrow at the foot of a giant camphor tree.

青柳 [あおやぎ] Aoyagi

鈴 [すず] Suzu

風呂敷 [ふろしき] wrapping cloth, cloth wrapper

虚海 [きょかい] Kyokai

慶東国 [けいとうごく] The Eastern Kingdom of Kei

Labels: 12 kingdoms, wind

September 11, 2005

Lost on location

Unfortunately, he jumped that shark about a decade after making his one truly decent flick, Under Siege.

Still, you've got to admire an actor who knows his niche, sticks to it, and stays busy doing what people will pay him to do. But there's another reason to admire the movie, artistic considerations aside: it was made in Japan by somebody who knows something about Japan. It's depressing when you realize how rare this is.

I was living in Osaka when Ridley Scott made Black Rain, a ridiculously inaccurate depiction of Japanese law enforcement and a waste of the talents of the great Ken Takakura. (Japanese police enjoy a breadth of latitude in arrest and interrogation that would give an ACLU lawyer a coronary. It's no accident that Japanese prosecutors have a 99.9 percent conviction rate, and mostly from confessions.)

A far better Takakura police drama is Station, in which he plays a Japan Railways transit cop. Add to the list Mr. Baseball, oddly enough, one of the better American films about Japan and Japanese corporate culture. Yes, Mr. Baseball plays to comfortable stereotypes, but far more accurate and instructive stereotypes than the uninformed and self-important nonsense in Black Rain.

Still, when Black Rain came out, I was looking forward to seeing something of my old stomping grounds. I didn't recognize a thing. Why they came to Japan to do the film is beyond me. They could have shot it with a bunch of extras on a set in San Francisco.

Ditto, Tokyo. Lost in Translation isn't the complete waste of time that Black Rain is, but neither can I keep up my interest when show business types start making angsty, self-referential movies about each other (in other words, if you can't top All That Jazz, don't try). As Dana Stevens sums it up in Slate,

Is it simply laziness, the same dearth of ideas that leads movie producers to base movies on 30-year-old sitcoms that no one really liked in the first place? The power of plain old sloth should never be underestimated, but one other explanation may be a variant on the fiction-workshop cliche "Write what you know." Perhaps industry types can only satirize what they know and loathe—themselves.

Like Black Rain, Lost in Translation is another movie made in Japan that has very little Japan in it. Again, it could have been shot on a soundstage and a couple of days at the New Otani Hotel in LA's Little Tokyo. Or just a second unit and a green screen.

Japan is supposed to be "Buddhist monks chanting, ancient temples, flower arrangement," Kiku Day wryly observes. Indeed, the movie comes across as director Sofia Coppola whining for 100 minutes that Japan didn't stay stuck in the 17th century like in the postcards, and pointing her finger like a kindergartener at the naughty Japanese not conforming to stereotype.

Into the Sun, on quite the other hand, takes us into Tokyo, through Tokyo, above Tokyo, and not the tourist trap enclaves that Lost in Translation conveniently sticks to. It's working-class Tokyo, the cramped little shops and narrow back alleyways.

To top it off, Steven Seagal has an excellent grasp of the language. At times the accent disappears completely—at least to my gaijin ears. They leveraged this nicely. A few early exchanges to establish that Seagal can talk the talk, and then (in scenes with native Japanese) Seagal would speak English and whomever he was speaking to would speak Japanese. It sounds goofy, but it worked for me.

It's a lot better than forcing Japanese actors to struggle though English dialogue. This ain't Shakespeare, but better that one's acting skills be spent on acting than trying to badly pronounce a foreign language. (In the interactions between Chinese and Japanese characters, they resort to English, which is indeed painful to listen to.)

Plus, Seagal's martial arts training permits him to move his hulking presence through the frame without looking like a timid bull in a China shop. Though I wish he would give up the guns 'n yakuza material and try something a bit quieter and more cerebral on for size. Say, a Chandler-esque detective solving gaijin crimes in Tokyo. Just rip off Sujata Massey's oeuvre. Seagal could make it work.

Related posts

Dances with Samurai

Japan's Bond legacy

The Pacific War on screen

Labels: japan, movie reviews, movies about japan, yakuza

September 07, 2005

12 Kingdoms update

Labels: 12 kingdoms, translations, wind

September 05, 2005

Pom Poko

I was reading my sister Kate's comments about animals-that-talk and thought I'll add another entry to the genre, Studio Ghibli's Pom Poko. It's easily their oddest film--to western eyes, at least--about a bunch of racoons trying to keep their land from being turned into a giant Tokyo subdivision.

I was reading my sister Kate's comments about animals-that-talk and thought I'll add another entry to the genre, Studio Ghibli's Pom Poko. It's easily their oddest film--to western eyes, at least--about a bunch of racoons trying to keep their land from being turned into a giant Tokyo subdivision.The movie takes place during the construction of Tama New Town, a real place. What makes it unique and rather disconcerting to anybody used to the typical Disney fare is that first, the story is told in the context of Japanese fairy tales that never went through the Victorian Bowdlerizing machine (a good review of tanuki folklore here). And second, we're not talking about the popular, western concept of "environmentalism."

In Japanese folk tales, the tanuki, or raccoon (slightly different but close enough), and the fox are depicted as tricksters and, more importantly, shape-shifters who can pretend to be human. The difference between the two is that if the fox is Dean Martin (cool), the raccoon is Jerry Lewis (comic relief). So this bunch of raccoons has considerable trouble getting their act together. And when they do, it's not pretty.

We're talking original Grimm-type material. Pom Poko is way more Terry Gilliam than Uncle Walt. The raccoon's shape-shifting can takes many forms, and includes the ability to do rather amazing things with their, ahem, testicles. The English dub manages to be more discreet than the sub, but I would bet that no official Disney kid's flick has ever before broached the subject.

The raccoons and humans end up killing a lot of each other, as in dead, and not the heartrending Bambi stuff. In other words, when anvils get dropped, heads get squashed (though squashed off screen). For the raccoons, it ends up being one pyrrhic victory after another. After all, Tama New Town ended up being built, so the outcome is pretty much predetermined.

What makes it far more than just another Road Runner & Wile E. Coyote cartoon is the very clever things the film has to say about how activists react differently to a cause, concluding with the futility of taking militant measures against a superior force. As my sister says about the Ewoks in Return of the Jedi, "Yeah, sure, Winnie the Pooh versus lasers. My vote is on the lasers."

It also points out the essential hypocrisy of high-minded environmentalism. There's a hilarious scene where the tanuki get distracted talking about all the great human stuff they can't imagine doing without (recall the "What did the Romans ever do for us?" scene from Life of Brian).

In the U.S., I think especially the left-wing of environmentalism is actually a mutated kind of Christian fundamentalism (the extremes of any movement eventually meet). Eden is recast as "wilderness," the perfect, people-less landscape before the Fall (or at least before 1492). In a country like Japan, there is no people-less wilderness, only places where lots of people don't happen to live right now (let's not even bring up the subject of whaling).

The question was not whether Tama New Town would be built, but what kind of place it would turn out to be. And the movie's surprising answer is that--thanks to the raccoons--it turned out about as well as could be expected.

Labels: anime reviews, environmentalism, kate, personal favs

September 04, 2005

What anime is really worth

Labels: anime, business, publishing

September 03, 2005

Gamera takes out Kyoto

Labels: japan, japanese movie reviews, movie reviews

September 01, 2005

Yet another "Harry Potter" exegesis

This was illustrated in a documentary I saw a while back about a real Air Force "Top Gun" school. One of the students was a brash twenty-something who obviously saw himself in the Tom Cruise role; another was a veteran B-1 bomber pilot, married with kids. Flying a B-1 is approximate to flying a 767, except the cargo is a bit different. But the "old guy" cleaned the young guy's clock in every single category. In the real world, age and experience make all the difference in the world.

I don't see this type of "Wise child" narrative as corrosive to the public order. I don't see it as especially conducive to good fiction either. You can thank it for all those Home Alone movies.

But I believe there another, darker reason for the popularity of Harry Potter. Rowling created a perfect storm of fiction's most tried and true genre plot devices, including the Wise child narrative (above), the Orphan (poor little rich boy) narrative, the Superhero narrative, and the Sports hero narrative. But the one that forms the structural foundation of Harry Potter's world, the engine driving the whole enterprise, is the Revenge fantasy.

The Revenge fantasy is an artistic tightrope, easily (and often) crass, exploitive and sexlessly pornographic (Death Wish). But at times ironic (Dirty Harry), poignant (My Bodyguard) and even profound (Unforgiven) in its sentiments. The Revenge fantasy is at the heart of most action flicks (Lethal Weapon), with the tipping point usually coming when a parent, child, or friend is kidnapped, assaulted, brutally murdered (Mad Max).

However, the Achilles heel of the Revenge fantasy is exactly the manner in which it must move the audience to condone, sympathize, and root for the "justice" the protagonist eventually meets out (extra-legal or not). Consider Mel Gibson's crucifixion scene in Lethal Weapon, in which he is spread eagle on a rack while being tortured by some thug. The brutality of this scene set us up for the next where he breaks the thug's neck.

We all know the bad guy had it coming. Except that wallowing in all this evil deadens the audience as well. This becomes apparent in the inevitable sequels. How to provoke the protagonist (and the audience) even further? The simplest way is by making his opponents even more depraved, the hero becomes more saintly in comparison, and his action justifiable. In Die Hard, a handful of civilians are murdered; in Die Hard II, hundreds are slaughtered. It gets numbing.

One way to mitigate this is to make sure that nothing really changes so that you can simply play the same emotional refrain over and over. Rowling has done both.

In Sergio Leone's spaghetti westerns, Eastwood's "man with no name" wanders from town to town. In this case, the Superhero narrative is meshed with the Revenge fantasy, as it is not enough to root out evil and bring it to justice--that would turn it into a police procedural--we must first be motivated to wish for what may be called the "payback" moment that comes at the climax, with one man taking on legions (Mel Gibson made a movie called just that).

Another good example is Shintaro Katsu's long-running samurai series, Zatoichi. Zatoichi is an itinerant gambler and masseuse, who also happens to be (natch) the world's best swordsman. In his bumbling, Columbo-esque manner, he wanders into town, stumbles onto some great injustice which he feels driven to right, leading up to a great cathartic sword fight in the last ten minutes of the film, during which he dispatches every bad guy in town.

At that point, were he to hang up his sword and settle down, that would be that. Were he were to come up with a more subtle way of righting wrongs, that would be that. But there's always another town where the politicians are exploiting the peasants and the yakuza are exploiting the politicians and somebody needs to clean house.

Still, once you've seen two or three Zatoichi films, you've pretty much seen all two-dozen plus. Again, the problem is that you've got to keep adding more sex, more violence, more outrages, more fights, more plot twists and turns to keep the story wheels turning. When Takeshi Kitano stepped into the role in 2003, he threw in a song and dance routine at the end. No kidding, a samurai movie with a chorus line.

Well, that indeed was different. Rowling's creative stroke in this regard is how she uses Quidditch to keep the fires stoked in between bad guy confrontations. This utterly illogical game exists to let Harry Potter be the star player, the quarterback on offense all the time, without the bother of him actually having to work and play well with others. Or even practice. Of his talent at the game, Rowling writes, "He realized he'd found something he could do without being taught."

Lucky him. But that's every kid's fantasy, isn't it? Hitting the long ball that wins the game, every game. And without all those workouts.

The Sports hero narrative is often a form of the Revenge fantasy, with athletic victory serving as a less-lethal kind of comeuppance. The sports arena allows the protagonist to beat his opponent physically and psychologically without invoking the morally troubling question of vigilantism. As in Rocky III, the hero is first humiliated by his opponent (the cartoonish Mr. T), and then, as the result of much righteous effort, pays his opponent back in the climax, literally eye for swollen eye and tooth for chipped tooth.

Harry Potter has all of the above working for him. He's an orphan, a sports jock, a superhero, and born to greatness. And rich. Not only are bad guys bumping off parents, friends, and then coming after him both as a child and a teenager, they don't even play fair! And that's just not cricket. Feel the outrage. Embrace the dark side of your human nature. Get them back for me. Go ahead, lop off somebody's head with your light saber (oh, sorry, wrong Revenge fantasy).

This, then, is why every new book is advertised as "darker" than the last, with some unexpected new violence or victim. It's also why nobody changes. Harry Potter doesn't mature, and neither does Malfoy, or the Dursleys, or Voldemort. They can't change objectives, change strategies, learn from past misadventures, reevaluate their places in the world, else risk Harry's revenge pilot light going out. They are locked into the caste system of the Revenge fantasy, doomed to relive the same parts over and over into eternity.

Or at least until the series ends.

Labels: book reviews, deep thoughts, harry potter, yakuza