December 26, 2005

More about names (12 Kingdoms)

字 [あざな] azana, an informal nickname adopted as a child (小字), or a formal nickname given by one's parents.

氏 [うじ] uji, the sobriquet you choose for yourself upon reaching your majority; this is a substitute surname, and the name by which you will be commonly addressed as an adult.

本姓 [ほんせい] honsei, lit. "original name," your surname as originally recorded (registered) upon the census at birth.

姓名 [せいめい] seimei, or "full name," or honsei + given first name; this is your complete, official name and never changes (sort of like a Social Security number). Traditionally, it was never used publicly, but some, like Rangyoku, use their given name instead of an azana.

Also critical to the discussion is the treatment of your given name in traditional Chinese culture:

According to the Book of Rites, after a man becomes an adult, it is disrespectful for others of the same generation to address him by his given name. Therefore, the given name is reserved for oneself and one's elders, while 字 [zi or ji in Chinese, azana in Japanese] would be used by adults of the same generation to refer to one another in formal occasions or writings; hence the term "courtesy name".

Note the following correction in chapter 2: "His [Chuutatsu's] registered family name was Son (孫) and his original uji, the surname he had chosen at adulthood, was Ken (健)."

This clarifies the following correction in chapter 21, the Royal Kyou addressing Shoukei: "And I take it this is Son (孫) Shou (昭)." Shoukei is enraged by this because the Royal Kyou has condescendingly addressed her by her honsei and without an accompanying honorific. (In Japanese, 昭 would be commonly pronounced "Aki," a girl's first name.)

Shoukei (祥瓊) is in fact her azana, derived from her official given name, Shou (昭). When Youko became empress, she formally adopted the azana, Sekishi (赤子). On the other hand, Keikei is a nickname (小字) or "child's azana" (though there's nothing derogatory about it). His formal name is Rankei (蘭桂).

As David Jordan explains the origins of the 小字 (in this particular context),

Children were sometimes given one or more derogatory nicknames designed to make them seem unattractive so as to avoid their being targets of attack by envious or malicious spirits. These names were, of course, rarely used past childhood, since they were temporary expedients.

Rangyoku is also her formal, given name, not an azana (a mistake I've fixed). As she tells Youko, "Old-timers hate being called by their given first name, but I don't care." Yet even Rangyoku will adopt an uji when she beomes an adult. (Here the etymology seems to part a bit from the Chinese, but the concepts are the same.)

Going back to chapter 2, the Royal Hou Chuutatsu originally took an uji of Ken. The modifier "originally" is necessary because people could take multiple uji throughout their lives. As a minister, his name was Ken Chuutatsu. I am assuming that Chuutatsu (like Sekishi and Shoukei) would have been his azana.

One note about Youko and her alias, Youshi. In Japanese, the trick is easy to pull off because the kanji (陽子) are the same. To avoid confusion, though, I've avoided using Youshi unless the author explicitly indicates that pronunciation, or if a person who only knows her by her alias actually addresses her by name.

UPDATE: It's been pointed out that while Youko's name never comes up in the dialogue in the latter two-thirds of chapter 24, it is written from Rangyoku's POV. I find this a compelling argument, so I'll try substituting in "Youshi" for "Youko" when the narrative meets that criterion.

Labels: 12 kingdoms, honorifics, japanese, language

December 25, 2005

Chapter 25 (A Thousand Leagues of Wind)

According to modern definitions, 1 畝(bou) = 30 坪(tsubo), or 30 x 3.31 = 99.3 square meters. 1 are = 100 square meters (or yards). Based on Youko's 135 cm number, the math doesn't work out as neatly as I would like. But as Enho explains, the length of 1 歩(pu) is relative to a man's stride, so the metric equivalents are close enough (one meter = one yard).

According to modern definitions, 1 畝(bou) = 30 坪(tsubo), or 30 x 3.31 = 99.3 square meters. 1 are = 100 square meters (or yards). Based on Youko's 135 cm number, the math doesn't work out as neatly as I would like. But as Enho explains, the length of 1 歩(pu) is relative to a man's stride, so the metric equivalents are close enough (one meter = one yard).1 跿(ki) = 1 stride

2 跿(ki) = 1 歩(pu) "pace" = 135 cm (according to Youko's calculation), but I'll call it one meter (yard) for the sake of simplicity

1 里(ri) = 300 歩(pu) paces

Note that ri can mean a measure of linear distance, a measure of area, or a "hamlet," all depending on context. Essentially, "hamlet" (里) is used in a political context and "well brigade" (井) in an agricultural context; ri (area or distance) is a geographical definition.

1 畝(bou) = 100 square meters = 1 are (about half a singles tennis court)

1 夫(pu) = 100 畝(bou) = 100 are = 1 hectare = 10,000 歩(pu) square paces

1 夫(pu) = 1 allotment (two American football fields, or a little less than one soccer field)

9 夫(pu) = 1 square 里(ri) = 900 畝(bou) = 90,000 square paces

9 夫(pu) = 1 井(sei) = 1 well brigade or 1 hamlet

3 hamlets = 1 village

According to modern definitions, 1 寸(sun) = 3 cm. However, the way Enho describes it, the width of a finger, 1 寸(sun) is closer to 1 cm. Similarly, 1 升(shou) = 1.8 liters, but described as the amount of liquid you could scoop up with your cupped hands, it's probably more like half a liter or a pint.

1 寸(sun) =1 cm

1 尺(shaku) = 10 寸(sun)

1 丈(jou) = the height of an average man

公田 [こうでん] kouden, publically administered land on the commons, the yield of which becomes the tax obligation of the ri.

廬家 [ろけ] roke, privately held land on the commons

井田法 [せいでんほう] seidenhou, lit. "well and paddy law"

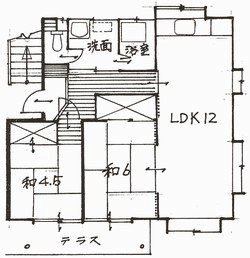

In Japan, real estate listings for houses and apartments include the letters LDK (or just DK). The letters stand for Living room, Dining room, Kitchen, often combined into a single room. The number preceding LDK is the number of bedrooms, so a 2LDK has 2 bedrooms, a living room, dining room, and a kitchen area. What makes this passage particularly funny is that, of course, it isn't Japanese at all, but English (though a usage unique to Japanese).

In Japan, real estate listings for houses and apartments include the letters LDK (or just DK). The letters stand for Living room, Dining room, Kitchen, often combined into a single room. The number preceding LDK is the number of bedrooms, so a 2LDK has 2 bedrooms, a living room, dining room, and a kitchen area. What makes this passage particularly funny is that, of course, it isn't Japanese at all, but English (though a usage unique to Japanese).The graphic is the blueprint of a Japanese apartment. The number following LDK is the floor area measured in jou (帖 or 畳), or tatami mats (85 cm x 179 cm or 3 by 6 feet). The kanji 和 stands for 和室 (washitsu) or "Japanese-style room," meaning that it has tatami mat floor. The rectangles represent the layout of the mats. A 洋室 (youshitsu) is a "western-style room," meaning it has a hardwood floor.

Labels: 12 kingdoms, wind

Chapter 24 (A Thousand Leagues of Wind)

数え年 [かぞえどし] kazoe-doshi, lit. "counting years"; the old manner of reckoning one's age, newborns being considered a year old, with everyone adding one year to their age at the New Year.

柳国 [りゅうこく] Kingdom of Ryuu (lit. "willow")

和州 [わしゅう] Wa Province

拓峰 [たくほう] Takuhou

蘇 [そ] So, Rangyoku's family name

Labels: 12 kingdoms, wind

December 21, 2005

Ikki Tousen

Watching this hilariously sordid show, I can only imagine that right from the start the producer sat down with the director and writing staff and said, All right, guys, male demographic, lowest common denominators, let's take the gloves off and cover 'em all (okay, I can't really imagine that because it's based on a manga, so it's all Yuji Shiozaki's fault, but they no doubt juiced it up plenty for television). In any case, here they are:

- A bunch of gang-banging, social-convention-shucking (but nonetheless obediently seifuku-wearing) high school students who moonlight as superhuman martial artists who leave holes in concrete walls with their fists. Ditto, the girls, only more so. (Check and check.)

- That whole "Grasshopper" thing with the cool old geezer chopsocky master. (Don't leave the monastery without one.)

- Never let the plot get in the way of the big fight scenes, consisting of:

a. Guys beating up guys. (Boring, but necessary.)

b. Guys beating up girls. (Whatever she's wearing getting liberally torn off in the process.)

c. Girls beating up guys. (Especially if he's twice her height and three times her weight!)

d. Girls beating up girls. (Obviously, much preferred to a, b and c.) - Whilst the fight is going on, lots and lots and lots and lots and LOTS OF PANTY SHOTS!! (Check, check, check, check and CHECK!!)

- Failing that, totally gratuitous nudity. (Like, totally, check.)

- Including a hot springs episode. (What, you think they would leave that out?)

- Naked lesbian high school chicks. (No, really, it's important to the plot!)

- Babelicious mom hitting on smart-ass high school jocks half her age (And you think your parents are embarrassing.)

- Wacko insane psycho-killer antagonist with a Gene Simmons fixation. (Are there any other kind?)

- Facing down a complete and utter ditz of a protagonist. (Completely and utterly check!)

Okay, I can hear you saying, so what? Another run-of-the-mill, been-there, done-that bit of pandering, low-brow shounen entertainment. Big deal. Most of what Enoch Lau might call the "PANTY SHOT!!" genre is pure dreck, unwatchable no matter how firmly tongue is pressed against cheek. What makes Ikki Tousen different is that these bottom feeders did a decent job on the animation, and settled on a boffo storyline. A good story beats just about any hand you can play.

The premise of Ikki Tousen has a bunch of high school students being possessed by the historical figures from China's Three Kingdoms era, and fighting the war all over again. Lasting from 184 AD to 280 AD, it was one of the bloodiest periods of civil warfare ever in human history. The military and political turmoil that arose out of it inspired the 14th century novel, The Romance of The Three Kingdoms, comparable in subject matter and literary importance to Tolstoy's War and Peace.

The novel had a profound influence on the historical narrative form both in China and Japan (including Fuyumi Ono's Twelve Kingdoms series). Another illustrative comparison might be Baz Luhrmann's Romeo + Juliet, in which the Shakespearean classic is set in the context of an L.A. gang war. Ikki Tousen, to be sure, has been tarted up and stripped (literally) of all subtlety and nuance, but sticks to the Machiavellian complexities of the source material.

The result can be terribly confusing at first to the western viewer, especially since they use the Japanese character names, which over the centuries have strayed far phonetically from the Chinese originals. But the whole idea of placing these historical conflicts in a modern context, with the battles organized and fought as a particularly violent sort of double-elimination, extracurricular high school sport, is so unexpectedly clever as to drag you unwittingly along for the ride.

Lastly but not leastly, Ikki Tousen is cheekily (literally) honest about what it's up to. As I have mentioned, we end up rooting for a hero whom even the narrator somberly intones is a dimwit. What, everybody around her wonders out loud, are we doing risking our lives defending this airhead? What, indeed, are we doing watching it? Um . . . never mind.

Labels: anime reviews, personal favs

December 18, 2005

Chapter 23 (A Thousand Leagues of Wind)

Vestiges of this system survive today. Most notable is the koseki (戸籍), or local census record, where demographic information is recorded and constantly updated. Births, deaths, marriages, divorces, and criminal convictions are recorded in the koseki. A marriage is not legal until it is recorded on the koseki. Everything else is window dressing. To be sure, most governments do the same thing, albeit not so deliberately and meticulously. In the United States, when you move to a new state, you must register your car, register to vote, and pay property taxes to the local government.

But there isn't a government system that consolidates all that information into a single authoritative database that is stored, maintained and accessed at the municipal level. The koseki is based on the family unit, not on the individual, and thus functions as an detailed genealogy as well as a demographic database. For example, in the manga Kioku no Gihou by Sakumi Yoshino, Karen discovers that she was not an only child when she gets a copy of her koseki to apply for a passport and finds on it her dead brother's name listed above hers.

I'm referring to public databases. Your credit card company sure does know what it needs to. But credit card information has historically been more secure than the koseki. In the mystery novel All She was Worth by Miyuki Miyabe, the murderer easily assumes the identities of her victims by means of the koseki. Koseki security has been tightened considerably over the last two decades, both in terms of the kind of information listed and who may access it, but because koseki records are so widely dispersed, they remain vulnerable to "human engineering."

For foreign nationals living in Japan, the rules are far more strict. An internal passport known as a "gaijin card" must be carried on your person at all times (I carried one for three years). You must register with the local municipal office whenever you move (this database is actually separate from the koseki). In a typical "homeland security"-type overreaction, the Diet is considering digitizing these internal passports, so that your location will be tracked whenever you do business with any public institution (hotels, for example).

The police can demand to see your "gaijin card" at any time for any reason, and failure to produce it is grounds for arrest.

The guarantor system is also alive and well, the bane of any foreigner wishing to rent an apartment in Japan. However, this is less an historical artifact than the unintended consequences of "consumer's rights" legislation. Namely, housing laws that make it very difficult for a landlord to evict a tenant. It's turned into a running joke in the anime, Hand Maid May, but as a result, landlords not only demand outrageous security deposits, but also secure the rent the same way a bank secures a loan. It is practically impossible to rent an apartment if you can't find a Japanese citizen to sign on the line as your guarantor.

Filling the need instead are real estate agencies that buy blocks of apartments and sublet them to foreigners. Many target high-end business types, but in Tokyo and Osaka, you can usually find "gaijin houses" that rent studio apartments at quite reasonable rates.

令巽門 [れいそんもん] Reison Gate, lit. "command southeast gate," one of four entranceways to the Yellow Sea

巽海門 [そんかいもん] Sonkai Gate, lit. "southeast sea gate," the narrow straits between Kou and the Yellow Sea (unlike the Reison Gate, not an actual gate)

四令門 [しれいもん] Shirei Gates, lit. "four command gates," where each of the four headlands or capes on Kyou, En, Sai and Kou almost touches the Yellow Sea (which is not a sea but an island surrounded by impassable mountains).

烙款 [らっかん] rakkan, sort of like an ATM card

永湊 [えいそう] Eisou, port city in Sai on the Kyokai

順風車 [じゅんぷうしゃ] junpuusha, a wheel-like talisman affixed to the top of the mainmast of a boat that ensures smooth sailing

奏国 [そうこく] Kingdom of Sou

舜国 [しゅんこく] Kingdom of Shun

没庫 [ぼっこ] Bokko, port city in Sou on the Kyokai

清秀 [せいしゅう] Seishuu, lit. "pure excellence"

Labels: 12 kingdoms, history, japan, wind

Chapter 22 (A Thousand Leagues of Wind)

北韋 [ほくい] Hokui Prefecture

固継 [こけい] Kokei city (also known as Hokui)

遠甫 [えんほ] Enho, lit. "distant beginning"

窮奇 [きゅうき] kyuuki, lit. "cornered curiosity," a species of flying tiger (youma)

Labels: 12 kingdoms, wind

Chapter 21 (A Thousand Leagues of Wind)

蝕 [しょく] shoku, lit. "eclipse"; a shoku can be engineered on purpose by a wizard or kirin, as with Youko, but also occur as random, natural disasters, as with Suzu. As Rakushun explain in chapter 38 of Shadow of the Moon, "[A] shoku is when here and there get tangled up together."

乾海 [けんかい] Kenkai, the straights between Hou and Kyou

鹿蜀 [ろくしょく] rokushoku, lit. "Szechwan deer," a zebra-like creature

恭国 [きょうこく] Kingdom of Kyou, lit. "reverent kingdom"

供王 [きょうおう] Royal Kyou

珠晶 [しゅしょう] Shushou, Empress of Kyou, lit. "sparkling pearl"

連檣 [れんしょう] Renshou, lit. "series of masts"

霜楓 [そうふう] Soufuu, lit. "frost maple"

柳国 [りゅうこく] Kingdom of Ryuu, lit. "willow kingdom"

範国 [はんこく] Kingdom of Han, lit. "exemplary kingdom"

Labels: 12 kingdoms, wind

December 14, 2005

Where You can Put your Christmas Present

学会主宰より前口上

Introductory remarks by the committee chair

生活様式学会2001へようこそ。諸君は愛しい女性がベッドで眠っており、みずからはサンタとなってそっとプレゼントを傍らに置く聖夜、どのようにしてそのプレゼントを置いているだろうか。っていうか女性にそんな風にプレゼント渡す? 普通?

Welcome to the 2001 Lifestyles Research Committee Meeting. On Christmas Eve, while their beloved girlfriends are asleep in their beds, gentlemen dress up as Santa Claus and secretly place the presents next to them. Where and how should they place their presents? In other words, one of these ways or the customary way?

報告一

Report #1

一刻も早く気づいてほしいなら顔の横に置け

If you want her to notice the present as soon as possible, put it right next to her face.

【まぶたを開けたら2秒でリボン】

After opening her eyes, she'll spot the ribbon in two seconds flat

この日のために苦労して用意した贈り物だから一刻も早く気づいてほしい。そんな切ないサンタ心に最も忠実なのが、眠った女性の顔の横にそっと置くスタイル。これなら、起きて焦点が合うまで約2秒という脅威的なスピードでプレゼントと認識してもらえるから。

Because you worked hard to get her present ready for this day, you'll want her to notice the present right when she wakes up. Surreptitiously placing the present next to her face as she sleeps is the style most in keeping with the Christmas spirit. This way, when she wakes up, she will see the present in an incredibly fast two seconds.

報告二

Report #2

絶望から歓喜の絶頂へと導く頭上置きの妙技

Placing it above her head is the way to guide her from disappointment to the paroxysms of delight.

【聖なる夜の絶頂方程式】

The formula for the ultimate Holy Night

プレゼントは相手の視野から外れた頭の上に置くのがベストだ。なんだ、プレゼントないや……と一度絶望を味わってから贈り物に気づけば、その喜びは絶頂に達する。絶望+頭頂=絶頂。この方程式を熟知し喜びの絶対値を最大化してこそ真の贈り物上手と言える。

It's best to place the present above her head out of her line of sight. Her joy will reach its zenith if, after tasting the disappointment of there being no present ("Hey, there's no present!"), she then sees it. Disappointment (絶望) + crown of the head (頭頂) = euphoria (絶頂) [a pun on the kanji in those three words]. Those familiar with this method, maximalizing the value of joy, are said to know the true skills of gift giving.

報告三

Report #3

贈り物を人肌にあたためるふとん内差し入れ

Warm the gift with her body heat by placing it under the futon.

【こんなプレゼントがあったかい?】

Is this the kind of presents that needs to be warm?

お酒はぬるめの燗がいい。ならば贈り物だってぬるめがいいとは言えまいか。人肌にあったまった贈り物を手にすれば、女性の凍てついた心もあったまるはず。それにプレゼントだって人の子だ。あったかいふとんに寝かせてやれば、よりいい仕事をするに違いない。

Sake is best served warm. That being the case, couldn't you say that the warmer the present the better? When she picks up a present warmed by her body heat, her chilled spirits will also be warmed. So the present is like a child. Putting it to bed under a warm futon will do the job just fine.

報告四

Report #4

悪夢を呼ぶ胸置きで女性を真に大事に扱って

By placing it on her chest and beckoning bad dreams, you are in fact taking good care of her

【イービル・サンタの親心】

The parental love of Evil Santa

女性を甘やかしてはいけない。苦労もなしにのうのうと贈り物をゲットできるようでは、ダメな女になること必至。女性を大切に思うサンタなら、胸の上にプレゼントを載せるべし。胸に重みが加わることで発生する悪夢は、プレゼントの対価としてちょうどいい。

You mustn't spoil your woman. Letting her get complacent getting presents without earning them will inevitably be the ruin of her. If you are a Santa who cares about his woman, you should place the present on her chest. The nightmares that spring from the added weight on her chest will just about offset the value of the present.

[The superstition that a weight on the chest brings about nightmares is not unique to Asia. The root of "nightmare," mare, is a demon that causes you to have bad dreams by sitting on your chest.]

報告五

Report #5

枕との交換でクリスマス・ドリームの演出を

Replace her pillow with the present to produce Christmas Dreams

【メリーさんのクリスマス羊はトナカイの夢をみるか】

Will she see dreams of reindeer or Mary's Christmas lambs?

どうせなら物だけでなくハッピーな夢も贈りたいもの。そのためには、枕とプレゼントを交換しておく方法が最適。プレゼントから脳に直接強いX線(=Xmas光線)が放射されるため、女性は夢の中でトナカイやメリーさんのクリスマス羊と遊ぶことができるのである。

When material goods aren't enough and you want to present her with happy dreams as well. To do so, replacing her pillow with the present is just the ticket. With the the "X-rays" ("X-mas beams") radiating from the present directly into her brain, your woman will be frolicking in her dreams with the reindeer and Mary's Christmas lambs.

報告六

Report #6

伝統の靴下入れで正統派サンタの仲間入りを

Join the orthodox school of Santas with a traditional stocking stuffer

【先祖代々キリシタンクツシタン】

The ancestral Christian socks

正統派サンタを自認する以上、先祖たちが培ってきた美しい伝統作法を踏襲すべき。そう、靴下だ。睡眠者が枕元に吊していようがはいていようが、迷わずプレゼントは靴下の中へ。物がデカいと苦労するが、その場合こそ真のサンタになる好機だ。「サンタ苦労す」。

More than simply recognizing the orthodox school of Santas, we should be following the beautiful traditions and mores cultivated by our ancestors. And that's socks. You can stuff presents into the stockings hanging by the bedside, but to avoid any confusion, just put the present inside her sock. Although it might hurt a bit if it's a big present, that is the way to true Santa-hood. Because then you're a Santa-kurousu. [Great pun, hard to translate. "Santa" + 苦労 kurou ("suffering") + すsu (infinitive verb ending) = "Claus."]

報告七

Report #7

プレゼントの手渡しを口実に使った痴漢戦略

Use the personal delivery method to cop a feel

【赤い変質者】

The red Lothario (or: the red Groper)

プレゼントって手渡しが一番嬉しいじゃないすか。だから僕はベッドにもぐり込んで、女性が目を覚ましたら渡そうとしてただけなんです。いや、別にハレンチな行為をしてたわけじゃ……。言い訳も空しく変質者は逮捕された。2000年度サンタ便乗事件の一幕より。

Is handing over the present not the favorite part of the exchange? That's why I'll slip into bed with her, and when she opens her eyes, I'll say I just came to give her a present. No, of course not! With no ulterior motives in mind! Though if that excuse doesn't work, you could get arrested for assault. (Based on a episode from a 2000 incident involving an opportunistic Santa.)

報告八

Report #8

幻想的な情景作りで女性のハートはメロメロ

Create a fantasy scene that warms the cockles of her heart

【空中WHITE CHRISTMAS FANTASY】

A WHITE CHRISTMAS FANTASY in MIDAIR】

女性は常にwhite Xmasを夢見る生物。この特性を熟知し、女性の顔に薄い白布をかぶせ、贈り物は電灯のヒモに吊しておこう。これだけで、辺り一面の銀世界の向こうにぼんやりプレゼントが浮かんで見える幻想的な情景が完成だ。Xmasなんて結局イベントだからさ。

Women are always dreaming of a White Christmas. Being familiar with this propensity, cover her face with a thin, white cloth and hang the present from the light cord. That's all you need to create the spectacle of a present floating faintly in the wide expanse of a silvery snowscape. It will turn Christmas into nothing short of an event!

[Yes, the joke is that the picture depicts exactly what a body at a Japanese wake looks like, with the face covered by a white shroud.]

学会主宰より総括

Concluding remarks from the chairman

今日なし得ることは明日に延ばすことなかれ−−とはフランクリンの言であるが、そうなんだよねえ、クリスマス過ぎてプレゼント渡してみたところで、これってお歳暮? とか思われるのがオチだし……一度逃すと10年くらい恨まれるんだよなクリスマスって……とか愚痴を言っている場合ではない。

Said Benjamin Franklin, "Never leave till tomorrow what you can do today." This is not necessarily true. When you consider that, after Christmas, you've still got to give gifts at o-seibo [the traditional New Year's Eve gift-giving], it turns into something of a bad joke. And it's no use complaining that, let it slide once and you'll pay with a decade of miserable Christmases.

さて、総括である。

And now, to recap.

報告1【まぶたを開けたら2秒でリボン】は、でも一度寝返りを打たれたらもうアウトである。もっと寝相の悪い女性なら2秒どころではない。そこらへんが致命的。

Report #1. If she turns over in her sleep even once, the gig's up. For a woman even more restless, "two seconds" is wishful thinking. Putting it there could be fatal.

報告2【聖なる夜の絶頂方程式】は方程式に疑問あり。望と頭はどこに消えた。

Report #2. I have doubts about this formula. Where did the "hopes" (望) and "head" (頭) go to? [Riffing off the same pun above.]

報告3【こんなプレゼントがあったかい?】はむしろプレゼント君にとって好ましい行為なのでは。女性にとっては(少なくとも最初は)冷たいのでは。

Report #3. It may seem like a good deed to you, but to her (at least to begin with), that present's gonna be freezing cold.

報告4【イービル・サンタの親心】は悪夢をプレゼントするということか。面白いが、邪悪。

Report #4. Giving somebody nightmares for a present is interesting, but wicked.

報告5【メリーさんのクリスマス羊はトナカイの夢をみるか】は、クリスマス羊とはいかなる動物なのかという点ばかりが気になる。

Report #5. The only thing I'm wondering about is what kind of an animal a "Christmas lamb" is.

報告6【先祖代々キリシタンクツシタン】は、はいている靴下にデカいプレゼントが入ることを前提にしている時点で子供だまし。

Report #6. When we came up with the idea of putting a big present into somebody's sock while they're wearing it, we were just funning around.

報告7【赤い変質者】はプレゼントを渡すという主題そのものが変質している。

Report #7. There's something definitely twisted about this "giving presents" theme.

報告8【空中WHITE CHRISTMAS FANTASY】はファンタジック! 女性による賛同と喜悦の声が聞こえてきそうだ。人工ホワイトクリスマス。これ以上に気の利いたプレゼントがあろうか(いや、ない)。

Report #8. Fantastic! I can hear her cries of joy and approbation even now! A man-made White Christmas. Could there be a more effective gift than this? (No, there couldn't.)

というわけで今回の推奨スタイルは、あたかもすこぶる頭の切れる犯人が完全犯罪を企てるがごとき用意周到さに心臓が凍る思いのする【空中WHITE CHRISTMAS FANTASY】としたい。

Meaning, I intend to follow this year's recommendation, thoroughly prepare, and like a smart criminal pulling off the perfect crime, do my own heart-stopping "WHITE CHRISTMAS FANTASY in MIDAIR."

以上。

That's all, folks.

December 11, 2005

Chapter 20 (A Thousand Leagues of Wind)

Plus, it is accepted practice in the U.S. to transfer from a junior college to a university, or from a second-tier undergraduate university to a higher-ranked graduate school. However, in Japan, students who fail to score high enough to get into the college or university of their choice will often sit out a year (similar to "redshirting" in college sports) and take the test again. Such students are called rounin (浪人), or "masterless samurai."

High school regulations, called kousoku (校則) dictate everything from the style of school uniforms to the length of girl's skirts, the length of boy's hair, and may prohibit the wearing of jewelry and the coloring of hair.

Youko says, "She has homework six days a week," because in Japan a half day of school is still held on alternate Saturdays.

使令 [しれい] shirei, youma who serve the kirin

班渠 [はんきょ] Hankyo, one of Keiki's shirei; he first appears in chapter 5 of Shadow of the Moon, described as a "big dog."

Labels: 12 kingdoms, wind

Chapter 19 (A Thousand Leagues of Wind)

胎果 [たいか] taika, lit. "fruit of the womb," a person whose "parents" are from the Twelve Kingdoms but is born in China or Japan. How this happens is explained in chapter 50 of Shadow of the Moon.

太師 [たいし] Taishi, lit. "big (as in "fat") teacher" (Lord Privy Seal); in medieval China, the Taishi was also responsible for the education of the prince royal.

太傅 [たいふ] Taifu, lit. "big tutor" (Minister of the Left)

太保 [たいほ] Taiho, lit. "big protector" (Minister of the Right)

The convoluted history of Koukan, ex-Province Lord of Baku, is detailed in chapter 7.

This chapter reminded me of an old Peanuts strip in which Peppermint Patty (I believe) says to Charlie Brown, "Quit hassling me with your sighs, Chuck."

Labels: 12 kingdoms, wind

December 07, 2005

All in the anime harem family

The thought occurred to me while I was watching the fascinating anime series Elfen Lied (from the German elfenlied, "elf's song," the third syllable a long /i/), the opening ten minutes of which may be some of the blood-spatteringest ever. Some two dozen people get decapitated, dismembered and eviscerated in a row, sort of an extended version of the killer rabbit scene in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, except these guys seriously don't know when to "Run away!"

The thought occurred to me while I was watching the fascinating anime series Elfen Lied (from the German elfenlied, "elf's song," the third syllable a long /i/), the opening ten minutes of which may be some of the blood-spatteringest ever. Some two dozen people get decapitated, dismembered and eviscerated in a row, sort of an extended version of the killer rabbit scene in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, except these guys seriously don't know when to "Run away!"The killer rabbit in this case is Lucy, a mutant superhuman with a murderous chip on her shoulder and a case of amnesia that turned her into schizoid psycho killer. A cute psycho killer, naturally. She is rescued by Kouta and Yuka, completely unaware of the ticking time bomb they've just picked up, and taken to Kouta's family estate, where he had been living alone. They also take in Mayu, another basket case (human). A little while later, Nana, Lucy's sort of kinder, gentler version shows up.

That's when it struck me: this has got to be the weirdest-ever contribution to the harem genre. The harem genre is unique to Japanese Y/A shounen (boy's) fiction. The way it works is, usually through some contrived, sit-com circumstances, one guy ends up living cheek-by-jowl with a half-dozen or more tremendously attractive girls. Sort of like the crazy old lady on the corner with the cats, except that the protagonist collects girls; or rather, they end up collecting him.

We're definitely in Madonna/Whore territory here. The female protagonists are as chaste as nuns, rationing their sexuality with the discipline of an Orwellian regime (though sexually titillating characters or situations will be tossed in as often wildly inappropriate "comic relief"). And the guy is generally stuck at the emotional age of thirteen and is passive as a stump.

Of course, in the hentai (whore) versions, the lion is kept quite busy servicing the pride (and/or visa-versa). But hentai's bark far exceeds its market bite and strikes me as more a fantastical exercise in overcompensation precisely arising out of pervasiveness of its mainstream counterpart. For in the popular mainstream versions (again, published initially for the Y/A shounen market), glaciers outpace character development and no relationship is EVER consummated.

In the corresponding shoujo (girl's) genres, to compare, the relationships do generally go someplace. Slowly, to be sure, but ground is covered. Lessons are learned. Steps are taken. Take sex, for example. In His and Her Circumstances, Yukino and Arima eventually sleep together. As do Karin and Kiriya in the shoujo manga Kare First Love. And in the stupendously popular shoujo manga, Nana, the two primary boyfriend/girlfriend relationships are consummated by the end of volume 1.

It never happens in the harem. In an early episode of Ai Yori Aoshi, Kaoru and Aoi do sleep together, but they only sleep. And that's the last time that happens. The next thing you know, he's living in a girl's dorm (and not getting any there, either). In Tenchi Muyo, Tenchi gets hits on repeatedly by his female alien houseguests but hasn't yet gotten to first base on this or any other planet so far as I can tell. Nor does he seem to be trying very hard.

And who can blame him, when some alien warship is always inconveniently invading Earth and landing in the living room? Vandread, an equally broad comedic space opera series, does make some clever puns whenever the one guy-piloted mecha fighter "joins up" with one of the gal-piloted mecha, but don't count on any of the relationships moving beyond the metaphor. To start with, they're too busy battling the bad guys (and you apparently don't need men to get pregnant, anyway).

Abstinence as a plot ploy achieves a state of farcical excess in Maburaho (and goes over the top in the execrable Mouse), with our hero rejecting the explicit advances of three of his coed classmates. He provides no moral grounds for doing so, except, I suppose, he's offended that they don't want him for his mind. Okay, one of them does want him dead as well as bedded (it's complicated), but the other two are eager and willing, and one of them is all ready to move in.

What makes this even more bothersome is that a good reason other than an endemic case of cooties would make the farce funnier. Just as in Ai Yori Aoshi, Kaoru and Aoi having the kind of relationship you would expect of reticent nineteen-year-olds, not twelve-year-olds, would make for better story lines, even without losing the slapstick material. By the end of the series, Hand Maid May similarly begins to gnaw at you. What in the world doesn't Kazuya see in Kasumi? She's smart, funny, competent, cute. And she's human. Oh, yeah. Human.

And speaking of cooties, Masakuza Katsura, who penned the unexpectedly sweet Video Girl Ai, also concocted the often just annoying DNA2, whose male protagonist is literally (and I am using "literally" literally) allergic to girls. The exact same plot device is again deployed in Mario Kaneda's Girls Bravo (the kid actually breaks out in hives).

But the worst of the lot—because it pretends to some realism while going on and on (and on)—is Love Hina. Keitarou is a ronin (an unmatriculated high school graduate) trying to get into Tokyo University. When his grandmother retires from running a girl's dorm, she ropes him into being the live-in manager. Ostensibly, Keitarou will fall in love with one of the borders whom he (wrongly) believes once promised to attend Tokyo U with him, but frankly, it's guys like him that arranged marriages are for.

Brigham Young University (speaking here from personal experience), rated by the Princeton Review as America's "most stone-cold sober campus," is hotter than the Las Vegas strip compared to this bunch. Keitarou and his sort-of-significant-others are so feckless and emotionally inept and just dumb that I can't watch it without wishing that a psycho killer would move in and do something really decisive with a big knife.

The protagonist in the harem genre is often a student living alone or at a boarding school (Mahoromatic, Maburaho, Please Twins, Happy Lesson), a ronin studying for his college entrance exams (Love Hina) or a college student (Ai Yori Aoshi, Oh My Goddess, Hand Maid May, Elfen Lied). Between the regimented hell of high school finals and the regimented hell of corporate life is the one period of life during which a Japanese man pretty much has permission to do nothing the best he knows how.

As he will rarely consider marriage until he has "settled down" with a degree and a job, introducing sex, commitment and marriage at this point would only spoil the fantasy with too much hard reality. (And that "settling down" can take a while. Median age at first marriage in Japan is 30 for men and 28 for women; in the U.S. it is 27 and 25, respectively.)

Many a male high school student must dream of reaching this safe stage of life and staying there forever, like all those American Graffiti boomers who can't get over high school. The irony is that exactly what these Peter Pans are trying to avoid is precisely the point of the shoujo genre. Kinko Ito, professor of sociology at the University of Arkansas, points out that while shoujo stories primarily revolve around a "small number of characters . . . in intimate relationships," those found in

men's weekly comic magazines entail many characters [hence, the harem] and elaborate story lines. This is very similar to the games that boys and girls play. Boys engage in group games with rules, structures, and hierarchy while girls tend to form a group of a few and share intimacy.

One direction to take here is Rene Girard's theory of mimetic desire as applied to the psychological dynamics of the harem. Illustrating the proposition, Philippe Cottet observes that (paraphrasing his rough English translation),

the infatuated girl praising the qualities of her boyfriend to her girlfriends asserts the superiority of her happiness in order to confirm her own desires. Her friends, envious of this happiness, desire the aforementioned friend in turn. Their desire reinforces in the girl the certainty that he is the "one." The object is not anymore the undoubtedly rather banal boyfriend of Miss X, but an illusion arising from rival desires. Outside of this rivalry, at a place of observation not contaminated by this illusion, all will ask the question: What in the world do they all see in him?

That question is too often the only one remaining on the viewer's mind after the video ends. If the five supposedly grown women in Happy Lesson so badly want a child to fawn over, why not do it the old-fashioned way? Perhaps because every Peter Pan has his Wendy.

Still, from the obvious-on-its-face perspective, Cattet's reading of Girard may be spot on: the harem simply represents the universal male desire to be desired by attractive women, and the female desire to desire something that will reciprocate that desire, however juvenile the form of reciprocation. But I believe there's another fantasy at work here, one more deeply rooted in the psyche, one more substantively responsible for the popularity of this specific genre: the harem as family.

According to this formulation, the male protagonist is less a potential lover than a stand-in father/brother/son. Each of the women in the harem, in turn, represents one facet of the ideal mother/wife/sibling figure, from tomboy to sex kitten to kid sister to parent and traditional homemaker. There's usually a lay Shinto priestess or sword-wielding Zen master in there, too. And if the plot mechanics posit that if a pair within the harem pair off—the principal male and female characters—then they become the de facto parents (though with curfews and separate rooms).

In fact, the shounen/harem genre does much better dramatically when the principals start off somewhat committed to each other, making them proxy parents by design. Oh My Goddess (Belldandy and Keiichi) and Ai Yori Aoshi (Kaoru and Aoi) begin with the girl making the first move and the two of them living together—only living—before the houseguests/siblings move in. In the former case, Keiichi's sister and Bellandy's sisters; in the latter case, Kaoru's female college classmates.

But none of his male college classmates. The male lead fills all of the designated male roles.

Sometimes, though, there is no metaphor to decode. According to the premise of Happy Lesson, five twenty-somethings decided to adopt an orphaned boy (Chitose). However, Happy Lesson isn't the flipside version of Three Men and a Baby. It's "Five Women and a Teenaged Boy." This immediately suggests an Oedipal subtext, but the explicit image of mother-as-sex object is one projected towards the viewer and blithely ignored by the actors, though it can be raised as an external threat.

Sometimes, though, there is no metaphor to decode. According to the premise of Happy Lesson, five twenty-somethings decided to adopt an orphaned boy (Chitose). However, Happy Lesson isn't the flipside version of Three Men and a Baby. It's "Five Women and a Teenaged Boy." This immediately suggests an Oedipal subtext, but the explicit image of mother-as-sex object is one projected towards the viewer and blithely ignored by the actors, though it can be raised as an external threat.One episode of Happy Lesson has a seedy real estate agent trying to blackmail Chitose with photographs that could be easily interpreted by the casual onlooker in very much the wrong light. This is seen as a direct challenge to the family structure (rather than an articulation of the patently obvious), and is fought with typical sit-com strategies and resolved with typical sit-com moralizing, again, emphasizing the primacy of the family unit above all other considerations, despite its artificial origins.

This kind of material plays on real-world taboos while staying on the side of angels. The tabloid press in Japan revels in stories of illicit teacher/students trysts as well as Oedipal (in Japanese, mazakon, or "mother complex") relationships getting decidedly out of hand, all reported with the expected hand-wringing salaciousness. On a base level, Happy Lesson is one long exercise in nudge-nudge, wink-wink.

In Hanaukyo Maid Team, the nudging and winking is done with a two-by-four to the back of the head. After his mother dies, Taro inherits his grandfather's mansion and its all-female staff. So predictable is this setup that all the characters could be cut and pasted from Love Hina or Happy Lesson or Oh My Goddess, with slight adjustments to hair color. There's Mariel, the "maid in chief," who becomes the mazakon figure, a clutch of spunky sister figures, the stern authority figure, and a trio of sexually precocious "personal assistants."

As for those latter three, this time around the whole cooties thing does make sense, as Taro appears to be about the age of eleven. But it also makes the running attempted statutory rape gag less than amusing. There certainly is no accounting for what some people think is funny. Or what constitutes "children's programming" in Japan. Or if it's not for children, what in the world the adults are reading into it.

But as noted above, the odds of sexual desire being acted upon within the harem are exactly zero. The taboo is purified and expunged, the impulse transformed into an expression of amae. Amae is the root of amaekko, or "spoiled child." As a verb, it can be used transitively, meaning "to mother" or "to indulge," and also intransitively, meaning to be put in the position of being pampered or taken care of. It describes a mutually dependent relationship (with the male making the token effort of rejecting it).

The expression of amae within the genre is the tried and true recipe for family formation. In Hanaukyo Maid Team, the family unit is first defined by Mariel, as substitute mother, making the newly-orphaned Taro her amae object. Later, a vulnerable "younger sister" (Cynthia) is introduced, becoming his amae object. Then the stern, father-figure (Konoe) warms to Taro and he comes to her rescue in turn. The family grows as each member demonstrates its willingness to take care of and be taken care of.

The rule-proving exception is Fruits Basket. I call it an exception because it follows the harem formula but comes out of the shoujo (girl's) category. Orphan Touru is taken in by the Souma family, three male cousins who share an ancient Chinese curse—they change into creatures of the Chinese zodiac when hugged by a non-clan member of the opposite sex. So right from the start, the asexual nature of the household is ensured.

Although a tenuous romantic relationship does eventually grow between Touru and Yuuki, her primary role is that of sister and mother figure, who starts out being rescued (the amae object) and ends up rescuing them (the amae giver). Despite its Pollyannaish gloss, Fruits Basket (and this is true of the shoujo genre in general) is far more sophisticated about the intricacies of human relationships than most shounen products. Touru eventually exerts a maternal influence on the entire clan, putting her into conflict with its tyrannical (and emotionally repressed) male head.

As with Fruits Basket, this theme of the "discovered" or "invented" family, often centering around the orphan/missing parent motif, turns up in genres far removed from the shounen "harem."

A case in point is My Dear Marie, in which Frankenstein-wannabee Hiroshi invents an sentient, anatomically-correct android girl to be his . . . sister. At the other end of the age spectrum, junior high student Nana of Nana 7 of 7 isn't an orphan. Her parents are working overseas, another common plot device. She is living with her mad scientist grandfather when she accidently clones seven copies of herself, each with a unique personality. In other words, she's now got seven sisters.

In Figure 17, another pre-teen shoujo title, Tsubasa moves with her father to Hokkaido after her mother dies. There she stumbles onto a secret escaped alien monster recovery operation (again, it's complicated). In the process, she accidentally "actives" Hikaru, a super-duper monster killer whose avatar looks just like her. Advertised as a girl-oriented superhero series (e.g., Sailor Moon), the show spends far more time chronicling the normal sibling relationship between Tsubasa and Hikaru.

Kaoru in the aforementioned Ai Yori Aoshi is an orphan. Suguru in Mahoromatic is an orphan, as are Toru in Hanaukyo Maid Team, Chitose in Happy Lesson and Mike in Please Twins. Just like Chitose, Mike (he's half-Caucasian) has returned to the town of his birth and scraped together enough money to rent the house he grew up in. One day, two girls show up on his doorstep, each claiming to be his long-lost twin sister. Of course, both end up moving in. Mike becomes father, brother and potential lover to the girl who isn't his sister, a possibility perpetually postponed.

In the opening episodes of Tenchi Muyo, Tenchi is living alone with his grandfather when the crew of alien girls move in. His mother died when he was young and his ne're-do-well father absconded. In Read or Die (the television series), Michelle, Maggie and Anita (all orphans) live together as sisters. It's several episodes before we realize they are not even related. When Anita rebels against the pretense, Yomiko tells her, "You have the kind of relationship I would want if I had sisters."

Elfen Lied takes this formula to the extreme. The mutation that gives Lucy and Nana their superhuman powers also programs them to kill their parents. So they're all orphans (except for the horrifically empowered Mariko, whose father is one of the mad scientists).

In particular, Elfen Lied and Mahoromatic share several highly informative similarities (besides the gratuitous nudity). Mahoromatic is the more conventional of the two series (according to manga/anime standards), and more comic than dramatic. Mahoro is a combat android, essentially a killing machine created to fight a secret alien invasion of the Earth. The initial battle won, and with only a year left on her life span clock, she retires and moves in with Suguru, the son of the man who had been her commanding officer, ostensibly as his live-in maid.

Mahoro and Suguru then proceed to collect a stable of other characters around them, filling out the familial and sibling roles (see accompanying graphic).

Mahoro and Suguru then proceed to collect a stable of other characters around them, filling out the familial and sibling roles (see accompanying graphic).Both stories play out against the background of (yet another) fiendishly complicated conspiracy to take over the world. Both Mahoro and Lucy are burdened with guilt arising out of violence they inflicted on the protagonist's family, that left Suguru and Kouta orphans. The important difference in their behavior is that Mahoro's intact conscience now leads her to compensate with an motherliness towards Suguru (when she's not dating him), though the relationship ultimately resolves with Mahoro playing a purely parental role.

Lucy's conscience, in contrast, has become binary. She is either childish and innocent (her mere presence literally disarming of her sister mutants), or knowledgeable and ruthless, a doll-faced, pitiless Shiva. She first discovers her powers when, as a elementary school child, she slaughters a gang of kids teasing her. She then goes on a killing spree, with her reductive reasoning leading her to simply walk randomly into a house, kill its occupants, and live there until she is discovered or runs out of food.

When Kouta takes her in, she has reverted to her childish mode, thus making her the object of amae. Kouta's only romantic attachment is to his cousin, Yuka, and so, as the formula dictates, he takes on a strong, paternalistic role. The next addition to the family is Mayu, fleeing child abuse, so also an amae object. Nana, Yuka's genetic kin, who still possesses a conscience, which makes her vulnerable to Lucy's rages, has been abandoned by her mad scientist guardian who, a la Snow White and the Woodsman, was supposed to kill her.

Writer Lynn Okamoto and director Takawo Yoshioka have taken a well-worn genre and sculpted from it a very Grimm tale (as well as a clever retelling of the Prodigal Son), spinning the wheel of fate between the destruction and creation of the world as symbolized in the annihilation and karmic rebirth of the family. When Mariko, the last and unredeemable mutant, is suicidally destroyed by her real father, the only human she spares after slaughtering all parental pretenders, time again moves forward and the family is reborn.

Indeed, Mayu confirms the thesis when she plainly tells Yuka, "You are the mother and Kouta is the father of this house."

It has become a tale for our time. Dystopians once imagined a Brave New World of globally-rationed reproduction. Remember Paul Ehrlich? Soylent Green? I predict that future historians will note that such schemes were attempted over the course of a quarter-center in China, but that China soon started frantically scrambling in the opposite direction as socio-economic factors made coercion mute and the birth rate plunged below replacement.

Instead, we are facing a future unimaginable only decades ago, one devoid of brothers, sisters, cousins, aunts and uncles. With a fertility rate of only 1.29, out of every five Japanese families with at least one child, only one will have two children. The more rare a thing is, the more prized, and the more impossible it becomes to recover. The harem genre echoes a desire for the large, "traditional," extended family that may soon exist only in fairy tales.

Labels: anime, deep thoughts, demographics, sex, shinto, social studies

December 06, 2005

Elfen Lied & Gustav Klimt

The top graphic is from The Kiss by Gustav Klimt. |

The Elfen Lied version is an almost exact reproduction. Note especially the positions of the hands and fingers. |

Here is a point-by-point comparison with Klimt's oeuvre.

Labels: anime, personal favs, pop culture

December 04, 2005

Chapter 18 (A Thousand Leagues of Wind)

Youko will tell Keiki essentially the same thing in chapter 20, and uses a very good example about how meaning springs from context.

Consider how most English-speaking students of Japanese learn the second person pronoun. Now, English pronouns are hardly the epitome of logic, especially when it comes to case. (Frankly, as with "you," English could pretty much dispense with case and hardly anybody would notice. Most native English speakers have enough trouble knowing when it's "you and I" or "you and me.") But at least "you" is a socially neutral term that can be used equally with a friend or lover, the pope or the president.

The temptation, encouraged by some Japanese teachers trying to press English and Japanese into the same grammatical mold (the same mistake English grammarians made when they applied Latin grammar rules to English, a Germanic language), is not only to translate "you" directly as anata, but to use the pronoun with the same diction. But anata is a familiar term, mostly inappropriate in civil discourse. It's how wives address their dimwit husbands in Japanese sit-coms: A-na-ta! It's not how you talk to your teacher or your boss or anybody with a higher social status than yourself.

Because Japanese instruction often focuses on grammar rather than diction, students learn anata incorrectly and go on using it incorrectly. And because gaijin speaking Japanese still have something of a sideshow quality about them, Japanese tend to grin and bear it rather than correct you. But if the grammatical parallels were abandoned early on, not only would students not be encouraged in this egregious bit of language transfer, but they would have start thinking differently about how language and culture interact.

(So how do you address someone with a higher social status without using the second person pronoun? Either by title, or drop the subject completely. Subjects, especially pronouns, are optional in Japanese.)

采麟 [さいりん] Sairin, kirin of Sai (才)

揺籃 [ようらん] Youran, lit. "rocking cradle"

Chapter 17

失道 [しつどう] shitsudou, or "Loss of the Way," the illness that afflicts a kirin when the king violates the Divine Will. The Royal En explains its implications in chapter 59 of Shadow of the Moon.

恭国 [きょうこく] The Kingdom of Kyou

供王 [きょうおう] The Royal Kyou

Labels: 12 kingdoms, honorifics, japanese, language, pronouns, social studies, wind

December 01, 2005

Problems with patrilineage

A government panel on imperial succession has issued a final proposal to revise the Imperial Household Law . . . . The immediate effect of the revision would be that three-year-old Princess Aiko, the Crown Prince and Princess' only child, will become the nation's first female emperor since female Emperor Go-Sakuramachi, who reigned from 1762 to 1770.

The real problem is a tricky one of patrilineage:

All those who succeeded to the Imperial throne, with eight female emperors counted among them, had emperors on their fathers' side, including cases in which their emperor ancestors were more than one generation apart. Traditionalists place the biggest importance to this unbroken male line of emperors, or "Bansei Ikkei," literally one line through all ages.

But to maintain the male line only with children born to emperors and their wives was often difficult. Nearly 60 emperors were children born to emperors and their concubines, including the Emperor Meiji and the Emperor Taisho. The current Imperial Household Law, enacted in 1947, excludes the concubine system.

Of course, some people aren't happy:

Academics and other commentators Friday blasted a government panel's recommendation that women and their descendants be allowed to ascend to the Chrysanthemum Throne, claiming it would break with tradition.

And, hey, if it worked before:

The question is whether it is the right thing to change our unique tradition and and history so easily," the Emperor's cousin, Prince Tomohito, wrote in a recent essay distributed to palace officials. "Using concubines, like we used to, is one option. I'm all for it, but this might be a little difficult considering the social climate in and outside the country."

You think? As you might imagine, though, overall public opinion is pretty favorable (towards a female monarch, that is, not towards concubines).

And speaking of the kid in question, the less she gets involved in these nasty palace intrigues, the better:

Japanese Prince Akishino has said he seldom talks to his brother Crown Prince Naruhito . . . . Naruhito took the unprecedented step last year of saying [Crown Princess] Masako was being deprived of her personality since she quit her promising diplomatic career for palace life. Akishino [then publicly] took his brother to task, saying he should have first consulted their father, Emperor Akihito.

On the plus side, she won't have to bother with this empress business for another half century or so, minimum, and who knows what the world will be like, then? I'd bet Prince Charles is just as happy warming the bench as sitting in the hot seat, as well.