May 28, 2006

Part 17 (A Thousand Leagues of Wind)

Chapter 68

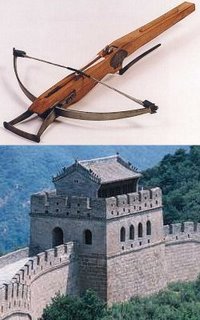

Chapter 68The stirrup of a crossbow is the D-shaped metal strap attached to the nose to hold the crossbow down while the bowstring is drawn back.

Chapter 67

The guard tower described in this chapter follows the same design as those found on the Great Wall of China. Note the alternating merlons and crenels lining the roof.

建州 [けんしゅう] Ken Province

Chapter 65

I've changed my mind several times about the translation of shishi (師士), a nonstandard kanji compound. Etymologically, it means "master samurai" or "teacher samurai." ("Shishi" is also a homophone for "lion.") Based on the context, I've translated it as "praetorian." To quote from Wikipedia: "The term Praetorian came from the tent of the commanding general or praetor of a Roman army in the field—the praetorium. It was a habit of many Roman generals to choose from the ranks a private force of soldiers to act as bodyguards

of the tent or the person. For the praetorians, saving Shoukou is a matter of self-interest, as opposed to the provincial guard, who aren't eager to get killed propping up a corrupt governor.

of the tent or the person. For the praetorians, saving Shoukou is a matter of self-interest, as opposed to the provincial guard, who aren't eager to get killed propping up a corrupt governor.An allure or wall walk is the walkway behind the parapet of a castle wall.

Chapter 64

籍恩 [せきおん] Seki On

1. 主恩 [しゅおん] shuon, a gift from one's master

2. 殊恩 [しゅおん] shuon, a very special gift

3. 誅恩 [ちゅうおん] chuuon, lit. "executioner's gift"

There's some clever punning going on with the kanji in these words. The constant is the second character (on), meaning "gift." 2 is the kanji left on the walls of Shoukou's residence. Shoukou reads these kanji to mean 3.

Labels: 12 kingdoms, wind

May 23, 2006

Learning language the sumo way

Foreign rikishi [wrestlers] are not here to learn Japanese, but to learn sumo. But by learning sumo they have to learn Japanese. That's their motivation. Many students who learn in classroom studies don't know what to do with the language they learn.

Baseball players, on the other hand, come to Japan pretty much as temporary workers, with hopes of returning to the major leagues in the U.S. And though originally an "American" game, you don't need to speak a word of Japanese to hit a home run or catch a pop fly.

The foreign sumo wrestler, Miyazaki notes, has "no prior Japanese study experience before coming to Japan"; is placed in a "total immersion" environment, and "has to learn Japanese to survive." Consequently, he has a "strong motivation to learn" and will use whatever resources are available. As a result of these language acquisition strategies, sumo wrestlers "don't need a teacher or a dictionary. They just learn through osmosis."

This sounds like hocus-pocus, but it jives with my experiences as a missionary a quarter century ago. Before arriving in Japan, I went through a two-month intensive course in Japanese (having never studied it before). My teachers were earnest, but not very well trained, and the curriculum was based on the antiquated audio-lingual method. That was the end of my formal Japanese instruction for two years.

(Actually, I did look up words in the dictionary—all the time—but as the real world wasn't slowing down while I did so, toting around a dictionary did little for my real-time comprehension.)

I floundered the first six months or so, making little headway. Then out of the blue, my language skills jumped several orders of magnitude. Language acquisition does not proceed on a smooth, linear curve, but progresses in a sawtooth fashion (the classic example being the mastery of the past tense by children), which can't be easily scheduled and plotted in a classroom.

Now, full-bore immersion has its problems. A day of intensive instruction every month would have gone a long way toward preventing bad language habits (after two years I still didn't use the personal pronoun correctly, and didn't understand why itte-imasu didn't mean "going.") But I'm talking about a day every month, not 18 credit hours a week.

The second factor Miyazaki points to is perhaps more important, and it applies equally in non-immersion environments: language is the tool, not the objective. Well, it is the objective if you're a linguist. But unless your goal is linguistics, studying language for the sake of language will get you nowhere.

USC linguistic Stephen Krashen makes the same argument quite forcefully. Teachers and students who focus on grammar, he says, are deceiving themselves if they believe that language is learned through the study of grammar. In fact, whatever progress they make "is coming from the medium and not the message. Any subject matter that held their interest would do just as well."

When I returned to Japan to teach English, many of my fellow teachers were there on educational visas, which meant they attended about 20 hours of Japanese classes a week, or the equivalent of a full academic schedule. I couldn't get over how little headway they made, for all their work and classroom time. (About as little headway as our English students made.)

Most language instruction is completely generic and unfocused: a mile wide and an inch deep. But sumo wrestlers, Miyazaki points out, come to Japan "to enter a new profession," one that demands the ability to communicate in Japanese. Like missionaries, in the process, they first acquire the specific vocabulary required to work in that profession.

Of course, the supposed flaw is immediately apparent: outside your narrow field of expertise, you become pretty illiterate. To a certain extent, though, that's true of your first language as well. Jay Leno's "Jay-walking" bits prove that you can be "fluent" in a language, yet dumb as a stump.

It may seem counterintuitive, but such a corpus—a few inches wide and a mile deep—is ultimately far more useful to the language student. That's because the syntactical engine powering human language machine doesn't care what vocabulary it uses as long as it's got a lot of it in what Stephen Krashen terms "comprehensible input."

What Noam Chomsky identified as the Language Acquisition Device, the biological catalyst that enables the automatic acquisition of language by children in a language-rich environment, has in adults gone from a roaring jet engine to a puttering biplane. But it still works. It still flies. It just needs a lot more care and attention.

And attention is key—that focused effort that keeps you hitting the books. As Miyazaki says, the focus isn't the language, it's what you want to do with the language. Large anime and foreign film libraries are available from Netflix and with online bookstores such as Book 1 and Amazon, you can develop a specialty in any subject.

I'm a great fan of studying Japanese through manga. You can start with an elementary title and work your way through the series, concentrating on a single author(s) and genre. The story is ultimately going to matter more than the language or the grammar, and that's why you'll keep reading and studying.

Labels: english, japanese culture, language, netflix, sports, sumo

May 13, 2006

Haibane Renmei

In a small town in a mid-20th century Eastern European country is the "Old Home," an orphanage whose residents are known as Haibane, or "gray wings." The children are born from cocoons with no memories of their previous lives. They sprout flightless wings on their backs and wear glowing halos over their heads. They never venture beyond the city walls, and after an indeterminate span of time, vanish as mysteriously as they arrived.

In a small town in a mid-20th century Eastern European country is the "Old Home," an orphanage whose residents are known as Haibane, or "gray wings." The children are born from cocoons with no memories of their previous lives. They sprout flightless wings on their backs and wear glowing halos over their heads. They never venture beyond the city walls, and after an indeterminate span of time, vanish as mysteriously as they arrived.The story begins with the "birth" of the newest member of the orphanage, Rakka, and follows her life at the orphanage as she tries to remember who she is and what she is doing there. Couched as a modern fable--never digressing to explain itself--Haibane Renmei slowly evolves through the exacting study of character into a thoughtful and moving exegesis on the Catholic concept of purgatory and the inextinguishable possibilities of salvation.

The Catholic Encyclopedia defines purgatory as "place or condition of temporal punishment for those who, departing this life in God's grace are not entirely free from venial faults, or have not fully paid the satisfaction due to their transgressions." The definition does not differ widely from the Mormon concept of "spirit prison," and echoes a similar belief in the post-mortal efficacy of "penitential works."

According to its writer and creator Yoshitoshi ABe [sic], the idea for the series arose from his own salvific experience. Though he does not identify a specific religion, if the metaphor fits, I say use it. But I found it especially telling that the burden carried by one of the main characters turns out to be suicide. By carefully documenting her unconscious desire for absolution and the self-imposed hurdles that stand in her way, Haibane Renmei tells a powerful story of personal forgiveness.

UPDATE: Daniel Cronquist's book on the subject discussed here.

Labels: anime reviews, fantasy, haibane, lds, personal favs, religion

May 03, 2006

Scrapped Princess

Outsiders often observe a culture with sharper eyes than those in it. Gorgeously animated and smartly written, the anime series Scrapped Princess asks how we should react to an apocalyptic revelation that everybody believes is going to happen, but nobody is quite sure how or why. Without becoming ponderous or pontifical, Scrapped Princess delves into eschatological dilemmas that we "end times"-obsessed Americans often have trouble dealing with in other than heavy-handed Manichean terms (e.g. Left Behind, End of Days, Stigmata).

Outsiders often observe a culture with sharper eyes than those in it. Gorgeously animated and smartly written, the anime series Scrapped Princess asks how we should react to an apocalyptic revelation that everybody believes is going to happen, but nobody is quite sure how or why. Without becoming ponderous or pontifical, Scrapped Princess delves into eschatological dilemmas that we "end times"-obsessed Americans often have trouble dealing with in other than heavy-handed Manichean terms (e.g. Left Behind, End of Days, Stigmata).When we meet her, the titular princess, Pacifica Casull, is a bratty teenager on the run with her step-siblings, Shannon and Raquel. An ancient prophecy has identified her as the "poison that will destroy the world," and the "Church of Mauser" has decided to deal with any uncertainty about the interpretation of the prophecy by having her killed. As the story begins, a potpourri of assassins, mercenaries, and wannabee knights are in pursuit of the trio. In their sister's defense, Rachel proves herself a powerful priestess and Shannon a mighty paladin.

Two classes of archangels appear as well: Dragoons sent to protect Pacifica, and Peacemakers sent to carry out the will of the Church. But the most formidable of Pacifica's enemies is Christopher Armalite, an agent with the secret police, who eventually begins to question the rationality and morality of his actions. Yet another existential dilemma presents itself when Shannon's guardian angel, Zefiris, blandly informs him that he and their allies have been genetically programmed to rise to Pacifica's defense.

The question of predestination versus free will forms the central conflict of the story, a conflict that eventually extends to the entire world. It soon becomes apparent that this "medieval" civilization in fact is the remnant of a devastating conflict that occurred thousands of years in the past. Readers familiar with Dave Wolverton's Golden Queen novels (among others) will recognize the "back to the future" motif, along with Arthur C. Clarke's useful adage: "Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic."

With humankind trapped inside a Rousseauan bell jar, Pacifica must choose between the guaranteed safety of enforced innocence, and the perils of freedom and self-determination. But a fall from Edenic grace demands a sacrifice. In our iconoclastic age, fantasy is particularly adept at analogizing the complexities of scriptural symbolism. In this respect, Scrapped Princess finds the right balance, illustrating how the demands of prophecy, triggered by betrayal, are answered with blood and magic, culminating in resurrection and redemption.

I consider this no small achievement. In contrast to the ending of Scrapped Princess, I found the atonement scene in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe a weak representation of the material it was analogizing. I don't know if author Ichiro Sakaki intended the metaphor to be extended this far, but the European setting of the series, and the representation of the Church of Mauser as the return of the Holy Roman Empire ("neither Holy, Roman, nor an Empire"), makes it hard for me to believe he wasn't aware of it. In any case, it works wonderfully.

Related posts

The atonement of Pacifica Casull

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

Labels: anime reviews, apocalyptic fiction, eschatology, magic, personal favs, religion, science fiction