June 29, 2017

Feeling (too good) about ourselves

false results by a lack of understanding about what human beings can do to themselves in the way of being led astray by subjective effects, wishful thinking, or threshold interactions.

Recently in the Guardian, Will Storr took a closer look at California's [self-esteem] task force that spawned the whole crazy fad. He reports that the credibility of the of the nascent movement

turned largely on a single fact: that, in 1988, the esteemed professors of the University of California had analyzed the data and confirmed his hunch. The only problem was, they hadn't. When I tracked down one renegade task force member, he described what happened as "a lie."

The actual language used to describe the "lie" is considerably harsher. But it didn't matter. At the height of the self-esteem movement, the task force had "five publicists working full time" telling politicians (and Oprah) what they wanted to hear.

Tackling the subject in greater depth, Jesse Singal concludes in his recent New York magazine article,

Maybe the biggest problem here, whether one is discussing the waning self-esteem craze or the possibly burgeoning "grit" one, is the basic idea that some behavioral-science eureka moment will, on its own, do all or much of the work of solving big problems in education or the justice system or any other area rife with inequities.

As far as that goes, the self-esteem movement is one fad that never made it to Asia. As Lenora Chu points out,

"Self-esteem" doesn't exist in the Chinese lexicon, at least not in the way Americans use it. In China, a child's regard for herself is rarely as important as [are] stark evaluations of performance. Almost as if child-rearing were an Olympic sport, the Chinese rank children on everything from work ethic to Chinese character recognition and musical skill.

It's still common practice for Japanese high schools to rank students by test performance—and post the rankings in public. University entrance exam results are also posted in public, although using a numerical code known only to the student instead of a name.

In Japan, it all does come down to "grit," which has been at the core of Japanese education for a century. Known as gaman (noun, "patience, perseverance, self-denial") and ganbaru (verb, "to persist, to stand firm, to try one's best"), if you fail, it's because you didn't ganbaru enough.

As Singal notes, this sort of magical thinking can be just as problematic. But I think it is ultimately a lot more practical than the self-esteem approach. "Showing up (on time)" really is half the battle won.

Related posts

Dragon Zakura

Perseverance makes perfect

Labels: education, japanese culture, science, social studies

June 25, 2017

Prison of Dusk (1)

The Five Punishments (五刑) defined the penalties meted out by the legal system of pre-modern dynastic China. In their earliest forms, they involved (but were not limited to) tattooing, amputation of the nose, amputation of one or both feet, castration, or death.

Japan's Currency Act of 1871 defined 100 sen (銭) as equal to one yen. The ryou (両) was made equal to one yen (円) and taken out of circulation. The yen was defined as 24.26 grams of silver. At the current trading price, around US $10-$15. By the end of the 19th century, the yen was pegged at US $.50, also in the US $10-$15 range when adjusted for inflation.

The yen steeply depreciated during and after WWII. The sen was taken out of circulation in 1953 and replaced by the yen. One yen currently has a value of around one U.S. cent.

The organization of farming hamlets is described in chapter 25 of A Thousand Leagues of Wind. A hamlet typically consists of eight families who farm the eight allotments and one common area. Hamlets are usually only occupied in the summer during the growing season.

Shundatsu's tattoo uses the following characters: Kin (均) Dai (大) Nichi (日) In (尹). Tattooing is one of the penalties spelled out in the Five Punishments.

Labels: 12 kingdoms, economics, hisho, history, law, translations

June 22, 2017

To Sensei with Love

Just as informative are those genres that do not find close analogues abroad, or inspire opposite reactions. For example, in the "conventional" romance genre, the relationship between a teacher and student. The Hollywood version is typically described with words like "forbidden."

Even if we're talking about legal adults, any given episode of Law & Order involving a professor and a college student is likely to end with a dead body.

There are, to be sure, plenty of legal, ethical, and moral reasons for discouraging such relationships. But as Kate argues,

The American attitude is bizarre. Not because teacher-student relationships are a good idea. But because the stigma rests on a proposition that is unsettling in the extreme: namely, that any teenager before the age of eighteen is the equivalent of a child.

And yet, in Japan, it's a go-to plot device, and not one expressly designed to raise eyebrows or breach taboos. Less a May-September romance than May-July, it typically involves a girl who is a high school student (and thus a minor) when we first meet her. Or far younger, as in The Tale of Genji.

But Genji is a gentlemen—well, one who has bed just about every aristocrat's wife or daughter in Kyoto—so he installs the ten-year-old Murasaki in his villa and waits for her to grow up. Which, back then, wasn't that much older.

A modern version of this story is Bunny Drop. Tellingly, the implied May-September romance the series open with ruffles fewer feathers than the one it ends with (the manga series, not the anime), despite the age difference in the latter being half that of the former.

And unlike Genji, Daikichi is the perfect single adopted dad. It's one of those endings that leaves me curious about what the unwritten sequel would be like. (Keep in mind that "Murasaki" in Genji is generally considered to be the author's autobiographical Mary Sue.)

Bunny Drop dares to keep the subject grounded in the real world. More typical of the genre is I Married a Pop Idol. The book blurb reads as follows: "A young businessman meets a woman and falls in love, leading them to marry. But the man's wife is actually an idol in high school!"

Even frumpy NHK has gotten into the act, with the clumsily titled Ms. Sauce's Love (literally translated), a weepy May-July romance between a college freshman (Yudai Chiba) and a thirty-something (Mimura). Chiba is actually 28 to Mimura's 33, though I'd swear he looks 14, if that.

The manga series R-18 combines the May-July romance with another strange (to American sensibilities) trope, according to which the virginal protagonist writes an explicit sex column under a nom de plume. This year's Eromanga Sensei again leveraged the popularity of that particular idea.

And let's not even get started on the whole sibling romance thing.

But back to teachers and students, a realistic portrayal can be found in Makoto Shinkai's Garden of Words, which has the teacher breaking off the relationship before it can move to the "next level." (And Shinkai's Takao looks and acts more mature than Chiba's Masanao.)

Dancing around the taboo are stories that concoct an excuse for the protagonists to get married, as in the aforementioned I Married a Pop Idol and the obnoxious Please Teacher series. Or the less obnoxious but pornier and occasionally funny My Wife is the Student Council President.

Back in the real world, there's French President Emmanuel Macron, whose wife is 25 years older than him. They met when he was in high school. Okay, reality can be stranger than fiction. How about "real" enough to make a live-action movie? Say, of Kazune Kawahara's bestselling Sensei! manga.

The story centers on second-year high school student Hibiki Shimada, who is in love with her teacher Kosaku Ito, a cold man who seems to hate girls, but is actually kind. The story begins when she accidentally puts a love letter entrusted to her by a friend in Kosaku's shoe locker.

Whatever would happen to high school romance in Japan without shoe lockers? But seriously, the sociology behind the widespread acceptability of this particular romance genre does deserve a closer look.

Japan's consent laws can be easily misconstrued. The applicable civil code is little different than in the U.S. Compulsory education in Japan ends after junior high. Few teenagers leave school at that point, but the legal possibility may help erode the magical 18-year-old boundary.

More importantly, most teens in Japan haven't contracted special snowflake syndrome. Japan is a country where elementary school students are expected to walk to school by themselves. Zounds!

Alas, actor Keisuke Koide recently learned how unforgiving real life can be. A drunken one-night stand with a 17-year-old girl resulted in NHK and NTV yanking shows he was in. Netflix, which cast him in an upcoming big-budget series, "is considering how to respond to the scandal."

(Which sounds to me like they'll let the commotion die down and proceed as planned, counting on there being "no such thing as bad publicity.")

You see, that's not fiction. In a society that can superficially appear devoid of moral limits (when making believe), social expectations ruthlessly enforce the lines that must not be crossed (in reality). Japan has the lowest teen fertility rate in the world and an abortion rate half that of the U.S.

Apparently Japanese teenagers know the difference.

Related posts

Cheese! (part 3)

Kicking down the door

The student-teacher romance in manga

Labels: anime, japanese culture, japanese tv, law, nhk, romance, social studies

June 18, 2017

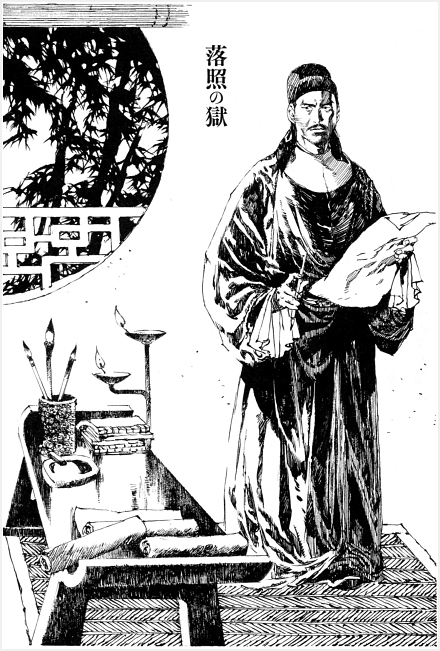

Prison of Dusk

"Prison of Dusk" (Rakushou no Goku) begins with a justice in the Kingdom of Ryuu trying to discern the motives of a serial killer (so the first half of an episode of Criminal Minds). Except the man is in custody and there are no questions about his guilt.

From there, the bulk of the story concerns the verdict in light of the weight of evidence (so the second half of a Law & Order episode). Justice Eikou and his magistrates must weigh public opinion against the emperor's own sentencing guidelines.

The problem is, the public wants the accused executed, and the faster the better. But the emperor has apparently taken capital punishment off the table.

From the start, the author dispenses with the typical red herrings and strawmen. The accused is definitely guilty, definitely remorseless, and understands the consequences of his actions. All that's left is the debate over capital punishment itself.

There's more dialectic here than story, and Fuyumi Ono pretty much leaves no rhetorical stone unturned.

And then toss in the twist that in the Twelve Kingdoms, bad things happening can literally mean that Heaven is casting a "no confidence" vote (it's the ultimate court of appeals). The result is a modern debate cast in medieval fantasy terms.

Labels: 12 kingdoms, hisho, law, politics, translations

June 15, 2017

Church of the extrovert

(In other words, my "activism" ends exactly at the point I'd have to get out of my armchair to do anything about it.)

On the other hand, a religion that promotes itself as having a "catholic" outreach must realize that differences in human nature exist. Unfortunately, it's easier to pursue utopian universality by pretending that everybody is (or should be) a clone of whoever's in charge.

As a case in point, an article about psychological depression in the Winter 2017 BYU Magazine uses missionary service to illustrate several aspects of the problem and then completely misses the point. Because one size fits all.

Consider the sidebar featuring the anecdote in which Lindsay, "a self-

The "advice" that follows never acknowledges that perhaps being "bold and assertive and confident" isn't for everybody and certainly not for every missionary. Instead, one is supposed to "increase resilience" and develop "coping skills." In other words, conform.

The coping strategies that worked for her--"spending time alone or reading a book"--are not allowed. Perversely enough, the only acceptable alternative this Hobson's choice offered her was to be labeled mentally ill.

To be sure, people have all kinds of issues, and being "with a companion 24/7 that [you] didn't choose, learning a foreign language, and adapting to a different culture" are some of the demanding pressures that inevitably come with being a Mormon missionary.

But, frankly, those pressures--which are finite in duration and not that much more demanding than the rest of post-mission real life--are peanuts compared to the expectations of unavoidable social engagement. And yet these expectations are simply never questioned.

Buddhism and Catholicism long ago figured out that there are convert-the-world types and there are vow-of-silence types. If you're one of the latter and find yourself in a church that's pedal-to-the-metal on the former, you're going to have problems, period.

The church of the extrovert is fine for those who are extroverts, want to become extroverts, or are willing to put up with being around extroverts. It's a Darwinistic gauntlet that systematically filters out the "unfit" personality types. That's fine too. It's a free world.

But if being the life of the party is the necessary condition the viability of the organization depends on, a church that prioritizes sociability and good PR may not be long for this earth. As Rod Dreher argues in The Benedict Option,

If believers don’t come out of Babylon and be separate, sometimes metaphorically, sometimes literally, their faith will not survive for another generation or two in this culture of death.

In his conversation with Albert Mohler about the book, he further explains:

My life is shaped around the chanting of Psalms and on all kinds of sensual ways that embody the faith. Of course you can have smells and bells and go straight to hell; that doesn't change you and lead to greater conversion. But for me as an Orthodox Christian and me as a Catholic, the faith had more traction and it drew me in closer and closer. I don't know if evangelicals can do that, because as I look at evangelicalism I see people who are zealous for the Lord, no doubt about it, but also susceptible to every trend that comes along.

(The "Benedict" Dreher refers to is not Pope Benedict XVI but the sixth century Benedict of Nursia. He founded the Order of Saint Benedict that defined the structure and objectives of monastic life and helped preserve Western Civilization through the Dark Ages.)

On the other hand, the Mormon church recently began dismantling its tight relationship with the BSA organization, and has hinted that it may divorce it entirely. So rejecting the popular secular option is always a possibility (though it remains increasingly unlikely).

Related posts

Up with introverts

The weirdest two years

Understanding Japanese women (and introverts)

Labels: buddhism, history, introversion, lds, religion, social studies

June 11, 2017

Hisho's Birds (4)

It was General MacArthur and SCAP that turned Emperor Hirohito into a public figure, after which the emperor's handlers proved themselves masters of public relations.

The modern Imperial Household Agency prefers bulletproof glass to bamboo blinds. This year, the annual New Year Greeting (which lasts about a minute) attracted almost 100,000 visitors to the Imperial Palace (not all at once but in five appearances).

Labels: 12 kingdoms, hisho, japanese culture, politics, translations

June 08, 2017

Bleep the bleeping bleep

Especially when it comes to language, it's hard to get offended by something when you don't know it is supposed to be offensive. (Is "bloody" a bad word?) It's all the more difficult when you don't know what the word means. And even when if you do, why is "shit" worse than "crap"?

In Japanese, the offensiveness of crude references to certain body parts shares close analogues in English. Otherwise, most "swear words" are only as severe as the context dictates. Whether a kid's manga or a hardcore yakuza flick, the translation of the above is the same: kuso.

I was reminded of this watching (well, mostly listening while working on my computer) the movie review segment on the Friday "Premium" edition of Asa-Ichi, NHK's morning news/chat show (it means "Morning Market," the shopping sense not the Wall Street sense).

Most foreign movies are subtitled when they debut in Japan (a few blockbusters and Disney animations hit the theaters in both subtitled and dubbed versions). So I'm typing away and all of a sudden, Huh? What?

I turn to the TV and on Asa-Ichi they're showing clips from a film written by a David Mamet wannabee (or maybe even by David Mamet). And nothing gets bleeped. I don't mind well-written cussing. It's just a shock to hear it smack in the middle of the morning.

If Good Morning America played unedited clips like this, the FCC would come down on them like a ton of bricks. And NHK is a pretty conservative outfit. You don't see nudity. Then again, nudity doesn't need to be translated.

Cussing, on the other hand, isn't cussing if it's in a foreign language! If anything, Japanese subtitles can be more coy than their literal Anglo-Saxon equivalents, hitting a zone of vague linguistic neutrality. It makes marketing sense to avoid needlessly offending the audience.

When it comes to manga and anime, sensationalist reports in the western press suggest an "anything goes" attitude, when the opposite is just as true. Relying on a 1907 law still in force, Japanese censors can be stricter and more arbitrary than the FCC, the MPAA, and the U.S. courts.

Ironically, Japanese-English translators often wander off into the weeds by striving for too much "authenticity," producing scripts for manga and anime (especially dubs) that toss in vulgarities not necessarily in the original.

Labels: japanese culture, japanese tv, language, nhk, social studies, yakuza

June 04, 2017

Hisho's Birds (3)

When used as a generic noun, I translate "shishou" as "master craftsman."

The reasons behind the exiling of women in the Imperial Palace, which set in motion the downfall of Empress Yo, are described in chapter 59 of Shadow of the Moon.

Labels: 12 kingdoms, hisho, language, translations

June 01, 2017

The tall and short of it

Average height in Japan over the past century demonstrates the importance of environmental factors. And having leveled off since 1960, the importance of genetics, though Yankees pitcher Masahiro Tanaka (6' 3") and Anne Watanabe (5' 9") handily beat regression to the mean.

Once a country climbs high enough up Maslow's hierarchy, genes do up to 80 percent of the heavy lifting (so say the geneticists). Over 423 genetic regions are connected to height and they mix and match in ways that are hard to predict.

Scientists like to study identical and fraternal twins to tease such things out. I would recommend studying haafu: the offspring of a Japanese parent and not-Japanese (non-Asian) parent.

There's an analogy here to how "Japanese" the child appears. Masao Kusakari, for example, regularly plays Japanese characters in NHK historical dramas. But I wouldn't have otherwise guessed that Risa Stegmayer has a Japanese mother (other than her speaking fluent Japanese).

My theory is that "averaging" kicks in when similarly functioning genes are mirrored at the same loci on both chromosomes in the pair. But if there's a null set on one of the chromosomes, the height genes take over.

Masao Kusakari is six feet tall (his father was an American GI killed during the Korean War), way above average for a Japanese born in 1950. Rangers pitcher Yu Darvish (Iranian father) is a towering six-feet-five.

But the award for comedic contrast goes to Jun Soejima, a presenter on Asa-Ichi, NHK's morning chat show. He hosts the Sugowaza Q (スゴ技Q) segment with Yumiko Udou, a Japanese woman of average height.

Jun Soejima (American father, Japanese mother) is six-foot-five. Wikipedia adds that his Afro adds eight inches, and also says that he traveled abroad only last year and doesn't speak English. In other words, height aside, a typical Japanese (yes, he played basketball in college).

Sugowaza Q translates roughly as "Super Skills IQ," about smarter ways to do common household activities like cooking.

Labels: japanese tv, medicine, nhk, science, social studies, sports