September 19, 2019

Red hair and redheads

Anime characters aside, actual human red hair (of the scarlet variety) is very rare in Japan. So while common hair colors like black (黒髪) and white (白髪) use kami, the ke (毛) in akage sets it apart from the norm.

The popularity of Akage no Anne after its publication in 1952 was such that subsequent translations have followed suit, and akage (赤毛) has come to mean "redhead" and all its related synonyms.

By comparison, the manga and anime Snow White with the Red Hair (「赤髪の白雪姫」) uses akagami. The association of akage (赤毛) with Anne Shirley is so pervasive that Sorata Akizuki (or her publisher) likely wished to avoid any confusion between the two literary redheads.

Related posts

Hanako and Anne

Mary Sue to the rescue

Snow White with the Red Hair

Labels: anime, anne, japanese, japanese culture, language

September 12, 2019

The orphan's saga

Anne of Green Gables has been a perennial bestseller in Japan ever since the publication of the first translation by Hanako Muraoka in 1952.

Anne of Green Gables has been a perennial bestseller in Japan ever since the publication of the first translation by Hanako Muraoka in 1952.The character of the spunky orphan (or a girl who becomes a "social orphan" when she sets off alone for the big city) has long been beloved in Japan. NHK built an entire franchise around the concept, with the Asadora morning melodrama now entering its sixth decade.

When it comes to cheerful and resourceful optimism in the face of punishing circumstances, Tohru from Fruits Basket is every bit Anne's equal. She needs to be when she ends up the only "normal" person in a household whose members are the actual animals of the Chinese zodiac.

The orphaned Takashi in Natsume's Book of Names (a guy for a change) has the ability to see the spiritual beings that haunt the Japanese countryside. Like Anne, he was fortunate enough to finally end up with adoptive parents who truly care for him.

The far less fortunate Chise in The Ancient Magus Bride has the same abilities as Takashi (a common trope). She was orphaned when her mother committed suicide and blamed her in the process. Little wonder she's a borderline basketcase when we first meet her.

The far less fortunate Chise in The Ancient Magus Bride has the same abilities as Takashi (a common trope). She was orphaned when her mother committed suicide and blamed her in the process. Little wonder she's a borderline basketcase when we first meet her.In a twist on Beauty and the Beast, the Beauty (Chise) is saved by the Beast (the monstrous Elias Ainsworth). Although Elias isn't exactly a rock of stability either. He's not even human, to start with.

Speaking of borderline basketcases, Rei in March Comes in Like a Lion is a shogi prodigy orphaned when the rest of his family is killed in an automobile accident. He turns pro in large part to get away from his screwed up adoptive family.

Rei is saved (psychologically) by an eccentric family of three orphaned sisters (mom died, father ran off) and their grandfather. And by the wealthy Harunobu, another shogi child prodigy who adopts Rei as his best friend. Harunobu is sort of an orphan himself, being raised mostly by his butler.

Rei is saved (psychologically) by an eccentric family of three orphaned sisters (mom died, father ran off) and their grandfather. And by the wealthy Harunobu, another shogi child prodigy who adopts Rei as his best friend. Harunobu is sort of an orphan himself, being raised mostly by his butler.And then there's Motoko Kusangai from Ghost in the Shell, who can be counted on to be resourceful in the face of punishing circumstances, though not necessarily very cheerful about it. In any case, she can count on her "family" from Section 9 to watch her back.

Related links

Fruits Basket (CR Fun)

Natsume's Book of Friends

The Ancient Magus Bride

March Comes in like a Lion

Ghost in the Shell: Arise

Hanako and Anne

Anne illustrated

The drama of the PCB

Labels: anime, anime lists, anne, asadora, books, japanese tv, social studies

September 05, 2019

"Anne" illustrated

|

| "Red-Haired Anne" (Anne of Green Gables) |

For her original translation published in 1952, Hanako Muraoka chose the title Akage no Anne (「赤毛のアン」). Due to the book's immense popularity, translations since have stuck with it.

|

| "Anne's Adolescence" (Anne of Avonlea) |

The kanji for "adolescence" is seishun (青春), literally "green spring." In this context, the word takes on an aura of classical romanticism tinged with sentimentality, the "blossom of youth."

|

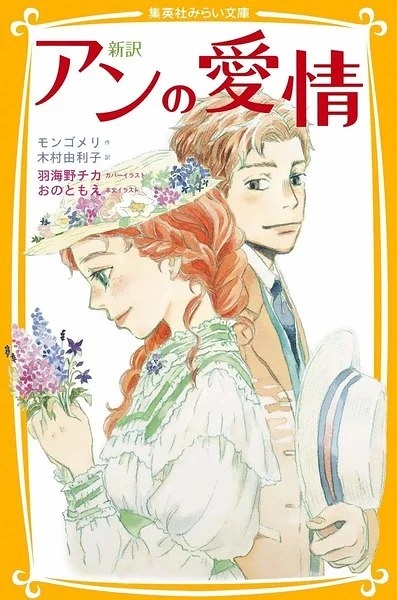

| "Anne in Love" (Anne of the Island) |

Though now a century old, Anne of the Island reads very much like a contemporary shojo manga, right down to the emphasis on competitive academic performance.

Related links

Honey and Clover

March Comes in Like a Lion

The orphan's saga

Hanako and Anne

Labels: anime, anime lists, anne, art, books, manga, publishing

November 01, 2018

Bakuman (the review)

We first meet Moritaka Mashiro and Akito Takagi in the ninth grade. Observing Moritaka's talents as an artist, Akito approaches him and proposes they team up to create manga.

Akito doesn't pluck this idea out of thin air. Nobuhiro Mashiro, Moritaka's uncle, was a mangaka with one published series and an anime adaptation to his credit. Then he literally worked himself to death trying to write another. "I'm not a mangaka," he often said with a wry grin. "I'm a gambler."

Moritaka's parents aren't eager for him to follow in his uncle's footsteps. Akito is also taking a leap. He is the school's top academic performer. Top academic performers aspire to attend Tokyo University, not become mangaka (this class conflict later gets its own story arc).

Helping Moritaka make up his mind is Miho Azuki, the girl he longs for from afar (or from across the classroom or from the adjacent desk).

With a helpful push from Akito, she reveals to Moritaka that she wants to become a voice actor. Moritaka promises to write a manga that will get made into an anime and Miho will star in it. Goofy, yes, but hardly out of sync with the mindset of a couple of ninth graders.

Taking place at arm's length, though, their romance is not terribly consequential in story terms. Rather like Gilbert in Anne of the Island, Miho remains mostly off-screen as Moritaka's muse.

A more emotionally compelling narrative follows the blossoming friendship between Akito and Kaya Miyoshi, Miho's classmate. They squabble like Anne and Gilbert from the first two Green Gables books. The blue-collar Kaya doesn't aspire to a whole lot, other than being with Akito.

But Kaya's down-to-earth nature keeps Akito and Moritaka and the studio on an even keel. Her relationship with Akito matures in a positive direction. It gives the series much of its heart and warmth. The series could have used more Kaya. And Miho needn't have been quite so absent.

The story does start with a few cheats. Moritaka's grandfather lends Moritaka the use of Nobuhiro's studio. Hisashi Sasaki, the managing editor at Shonen Jack, worked with Nobuhiro. So he knows Moritaka, though doesn't do him any favors, other than giving him a fair shot.

A fair shot at Shonen Jack, née Shonen Jump. From the start, Moritaka and Akito aim for the top.

Shonen Jump is the best-selling manga magazine in Japan. At its height during the mid-1980s, it sold a staggering 6.5 million copies a week. Though demographic changes have cut deeply into those numbers, Shonen Jump still boasts a weekly circulation of two million.

In the anime adaptation, the magazine is called Shonen Jack and the publisher is called Yueisha instead of Shueisha. The posters of One Piece and Naruto decorating the lobby walls make it clear what publication they're referring to.

Shonen Jump has a sister publication called Next, where up and coming manga artists can test out their talent. So does Shonen Jack.

One of Moritaka and Akito's submissions ends up on the desk of Akira Hattori. The junior editors at the magazine sort through the submissions to find mangaka with promise. The careers of the editors depend on how well they can develop a mangaka's career and sustain a successful series.

After asking for revisions, Hattori enters the manuscript in an upcoming contest at Next. These contests are another way of recruiting and judging new talent. Moritaka and Akito do well and are invited to submit a one-shot to the prestigious Tezuka Award at the main magazine.

They don't make the final cut but Hattori is sufficiently impressed to ask for more submissions.

In a highly iterative process that any old-school freelance writer is familiar with, they revise and resubmit, revise and resubmit until they get an acceptance. This process takes months, even years. So the the series often makes big jumps in the timeline from episode to episode.

Once they have established their bona fides as artist and writer, they are invited to submit a one-shot that could be serialized. Essentially a pilot episode.

Everything published in Shonen Jack gets rated. A steady stream of reader surveys are compiled twice weekly into spreadsheets. If a one-shot with serialization prospects delivers good ratings, the editor petitions his senior editor to present it at a serialization meeting.

But every new series means an existing one must be canceled. As the managing editor likes to say, "If you write a good manga, you will get published. But not necessarily by us."

While working on their projects and waiting for the thumbs up or thumbs down, mangaka often free-lance as assistants. The pressures of turning out two-dozen finished pages every week is such that, once serialized, a mangaka depends on assistants to do the inking and background work.

Eiji Niizuma is a boy genius, the same age as Moritaka and Akito. The managing editor personally recruited him to write for Shonen Jack. When we first meet Niizuma, he is a bundle of ticks and idiosyncrasies, a sort of artistic Sheldon Cooper after a dozen shots of espresso.

But he proves to be a great asset, both as a rival and a friend, with a keen eye for what works and what doesn't (though he's not very good at explaining why). During his short stint as Niizuma's assistant, Moritaka meets several of the other key players in the series (his competition).

First is Shinta Fukuda. Cocky and brash, a rebel in search of a cause, he appoints himself the leader of the new recruits. He aspires to write gritty urban dramas.

In his mid-thirties, Takuro Nakai is the oldest in their circle. He is the most technically proficient artist but hasn't ever been serialized. As each year passes, the odds grow longer and he grows more desperate, a desperation that has produced several self-destructive behavioral quirks.

He eventually teams up with Ko Aoki, who comes to Shonen Jack from the shojo manga side. (The real Shueisha publishes over a dozen manga magazines in all genres.) They get the green light for a series. The question is whether Nakai can hold his personal life together in the meantime.

Although working in utterly unlike genres, Fukuda and Aoki exemplify an important point that Bakuman makes about popular art. In dramas about "artists," the market-driven demands of the audience and the imposition of editorial constraints are typically cast as the bad guys.

In Bakuman they are the unavoidable—and not necessarily unwelcome—reality.

The immense popularity of Shonen Jump pulls in readers of all ages. But the shonen (少年) in Shonen Jump means "boy," the target audience being between ten and fifteen years old. "Fan service" is fine but no nudity. Action is emphasized but the violence can't get gory.

Fukuda could easily write for a seinen magazine, aimed at older teens and college students.

Takao Saito, for example, has been writing Golgo 13 for fifty years. A gritty series about a professional hitman, Golgo 13 runs in Big Comic, a seinen manga magazine. A circulation of 300,000 is nothing to sneeze at. But it is one-sixth that of Young Jump.

Aoki could easily write for one of Yueisha's shojo (少女) magazines. But the most popular shojo manga also have circulations in the mid-six figures. Getting published in Shonen Jump means reaching the biggest audience possible. It also means hewing to the magazine's editorial guidelines.

So her fantasy series must have more vivid action sequences and her romance series must have more fan service. In one of the funnier arcs, Fukuda takes it upon himself to tutor Aoki about how to appeal to the prurient interests of twelve-year-old boys (without outraging their parents).

These compromises are a constant. Action-oriented "battle manga" are the most popular. A mid-list "gag manga" has the most reliable staying power. But Akito turns out to excel at a Rod Serling approach, writing stories with a surreal or paranormal edge that are layered with social commentary.

At first, Hattori suggests that being "the best of the rest" isn't a bad place to end up. Except Moritaka and Akito want to compete at the top with Eiji Niizuma (everything's a competition in a shonen series). In the process, they give every genre a shot, frequently fail, and start over.

But this is a melodrama and not a documentary. They do finally find the success they are looking for. And their editors are there every step of the way. I can't think of another drama series about the arts that gives the lowly editors so big a role and makes them the good guys to boot.

And gives them so many smart things to say about what makes a story successful.

The original Bakuman was published in 176 chapters over four years. The anime ran for 75 episodes in three seasons on NHK Educational television. The art and animation can't match that of a dozen-episode cour from Kyoto Animation. But this is a series where the ideas matter more.

With so much material to generate, Tsugumi Ohba and Takeshi Obata often fall back on a problem-of-the-week approach to creating drama. While predictable, this is actually a great advantage of the series.

As a result, we get a crash course in every kind of manga, every issue, conflict, and editorial decision that arises in the manga publishing business. The constant search for new ideas, the stress of weekly ratings, the business decisions that go into making a manga into an anime.

And, yes, all those dysfunctional mangaka.

For example, Kazuya Hiramaru, who abruptly quits his job as a salaryman to write a surreal Dilbert-like gag manga about an otter in a business suit. Only to discover, to his horror, that he's abandoned one rat race to join another where the rats have to run even faster.

"At least when I was a salaryman I had weekends off!" he complains to his editor. But poor Hiramaru is cursed to be a talented and popular—if lazy and unmotivated—mangaka. So his Svengalian editor will stop at nothing to trick, coerce, and manipulate him into making his deadlines.

Hiramaru isn't exaggerating too much. As Shuho Sato documents in Manga Poverty, simply breaking even can take a mangaka years. Those assistants get paid out of the mangaka's page-rates. So turning a profit depends on how fast the mangaka can run his production line.

Sure, there will always be writers who produce best-sellers right out of the box and rake in millions. And I certainly enjoy following the adventures of the Richard Castles and Temperance Brennans, who somehow find the time to solve murder mysteries in between writing yet another best-seller.

But back in the real world, commercially successful art requires more work, discipline, single-minded determination, and, yes, creativity than most of us are capable of. Along with a large dose of luck. Which makes me all the more appreciative of those who can pull it off.

Related posts

Bakuman (the context)

Bakuman (the future)

Bakuman (the anime)

Manga economics

The teen manga artist

Manga circulation in Japan

The manga development cycle

Labels: anime lists, anime reviews, anne, art, business, japanese culture, publishing, tubi

October 20, 2014

L.M. Montgomery's free-range kids

I'd seen the latter too, which was in no way encouraging. Sullivan's Anne of Avonlea (also known as Anne of Green Gables: The Sequel) is a good example of how to deviate from the source material while keeping true to its substance and spirit.

The Continuing Story is a good example of getting it all wrong. Sullivan manages to turn Anne, as Kate puts it, into a "bucolic female James Bond." Yes, it's supposed to be about Rilla, but the lead had to be Megan Follows. Like I said, it's a mess.

Rather, Joe points to Rainbow Valley as the standout in the post-Green Gables books. So I clicked over to Project Gutenberg and downloaded it. And he was right. Rainbow Valley is a real gem.

As Joe points out, Rainbow Valley is less about the staid Blythe kids than the wacky Merediths. They're the offspring of the eccentric and widowed minister. Following the death of his wife, the children mostly raise themselves (not a social worker in sight).

Things only get dicier when Mary Vance shows up, the orphan girl they take in like a lost dog.

Mary Vance is the alternate universe version of Anne. While Anne coped by filling up on literature, focusing her mental energy inwards and fueling her imagination, Mary Vance turns hers outwards, with the goal of controlling the chaotic world around her.

Not surprising, given an upbringing that makes Anne's pre-Green Gables life look comfortable by comparison. Nowadays, Mary Vance would be cast as the pitiful victim on a Law & Order episode, a serial killer's childhood flashback on Criminal Minds.

"My grandfather was a rich man. I'll bet he was richer than your grandfather. But pa drunk it all up and ma, she did her part. They used to beat me, too. Laws, I've been licked so much I kind of like it."

Or pumped full of Ritalin and handed over to Child Protective Services. But a century ago, a tough childhood gave a kid "character." Indeed, Mary Vance isn't looking for excuses. To be a "victim" is to not be in control, and that's that last thing she wants.

Mary tossed her head. She divined that the manse children were pitying her for her many stripes and she did not want pity. She wanted to be envied.

With her considerable wit focused so long on day-to-day survival, the attendant niceties long ago went by the wayside. And so unconstrained by a still nascent superego, her id leaks out all over the place. She definitely gets all the good lines.

"Mr. Wiley used to mention hell when he was alive. He was always telling folks to go there. I thought it was some place over in New Brunswick where he come from."

"I haven't got anything against God, Una. I'm willing to give Him a chance. But, honest, I think He's an awful lot like your father, absent-minded and never taking any notice of a body most of the time, but sometimes waking up all of a sudden and being awful good and kind and sensible."

"Give me Daniel [in the Lions' Den]. I'd rusher have it 'cause I'm partial to lions. Only I wish they'd et Daniel up. It would have been more exciting."

"If one has to pray to anybody it'd be better to pray to the devil than to God. God's good, anyhow so you say, so He won't do you any harm, but from all I can make out the devil needs to be pacified."

As Miss Cornelia puts it, "If you dug for a thousand years you couldn't get to the bottom of that child's mind."

But Mary Vance hardly has the story all to herself. In the second half of the book, the misadventures of the untethered Meredith kids take over the story, along with the emergence of a possible romantic companion for their father (a sweet note to end on).

Reading Rainbow Valley is like listening to a gossipy small-town newspaper read aloud, the chronicler now and then stepping back from the narrative to offer an aside or two about her subjects. But always with the best intentions--and honest empathy--in mind.

Although I shy away from the omniscient point of view, Montgomery's relaxed command of the narrative is such that the "head hopping" never bothers me, and even imbues the story with a touch of magical realism that places it apart from the real world.

Though with the Great War just over the horizon, the book briefly breaks the reverie at the very end with a haunting bit of foreshadowing.

This was certainly a great part of Montgomery's appeal in Japan. Hanako Muraoka completed her translation of Anne of Green Gables during WWII. The Japanese edition was published in 1952. "Reality" was one thing they didn't need any more of.

Though as far as reality goes, Rainbow Valley hews closer to my own childhood (considerably less than a century ago) than the nanny state reigning today. Back then, the only parental constraint imposed on us as we flew out the door was: "Be home by dinnertime."

Labels: anne, book reviews, free-range kids, kate, social studies

September 29, 2014

Hanako and Anne

The series is based on a biographical novel written by her granddaughter, Eri Muraoka. The fictional version streamlines and simplifies her childhood, and goes out of its way to draw parallels between Hanako's life and Anne's story.

Hanako had seven siblings in real life, three in the series. As in Anne of Green Gables, the farming out of "excess" children to relatives was common practice. Hanako's daughter was actually her sister's child. Her own son died at the age of five.

This adoption (once quite common in Japan and still done today) is depicted in the series.

A Christian, Hanako's father had his daughter baptized into the Methodist Church (that part left out). From the age of ten, Hanako boarded at a missionary school for girls in Tokyo. The school, Toyo Eiwa Junior High and High School, still exists.

Like Anne, after graduating (with the equivalent of an associate's degree), she taught school before marrying and becoming a full-time writer. In the 1930s, she hosted a weekly children's program on NHK radio.

Hanako translated just about every popular work of young adult English literature published in the 19th and early 20th centuries, starting with The Prince and the Pauper and including Polyanna, The Secret Garden, and Anne of Green Gables.

Between 1927 and 1968, she translated two books a year on average. Published in 1952, her abridged version of Anne of Green Gables (completed in secret during the war) became a bestseller.

Over a dozen new translations and annotated editions of "Red-Haired Anne" (as it's titled in Japan) have been published since. The book appeared at exactly the right time in 1952 to leave a lasting imprint on the culture.

Hanako's life and career are also a good example of necessary and sufficient conditions coming together. Hanako was born with all the right tweaks in her Broca's area to make the most of a unique opportunity, and coupled that with tons of drive.

The television series depicts her as fanatical about learning English, far more than her classmates, which I think is exactly right. Nobody devotes that fabled "10,000 hours" to mastering a skill if they don't like it and don't consistently improve at it.

The series ends with the publication of Anne of Green Gables. Hanako traveled to North America for the first time in 1967. She died the next year at the age of 75.

The life of a translator is not all that interesting, so the series devotes a considerable amount of screen time to the real-life soap opera of Hanako's classmate and friend, Byakuren Yanagihara ("Renko" in the series), a cousin of the Taisho Emperor.

Their friendship reveals the sociolinguistic conventions of the time: Hanako always refers to Renko using the honorific "-sama" while Renko addresses Hanako using the diminutive "-chan."

Byakuren married three times. The first two were blatant exchanges of titles for money, her brother having screwed up the family finances. She ended the second marriage (to a coal magnate thirty years her senior) with a scandalous affair and very public divorce.

Along the way she published several collections of tanka poetry and became a vocal advocate for women's rights.

Stripped of her title, she lived a much happier life as a commoner (though was devastated by the war-time death of her son in 1945). She and her third husband were married for 46 years, until her death in 1967.

Labels: anne, asadora, japanese tv, language, nhk, radio, showa period

January 20, 2014

A bucolic female James Bond

The CBC production of Anne of Green Gables (1985) follows the novel pretty closely. But for Anne of Green Gables: The Sequel (sometimes titled Anne of Avonlea) two years later, Sullivan combined material from the next three books (mostly Anne of Avonlea and Anne of Windy Poplars).

I thought it worked rather well (and dispensed with most of Anne of the Island, that I didn't much like).

The compressed timeline required significant changes. In Anne of Windy Poplars, Anne has graduated from college and is hired as the principal of Summerside High School. But Sullivan did a good job weaving the themes together and paying off--even improving upon--the major plot points.

For Anne of Green Gables: The Continuing Story (2000), Sullivan tried to do the same thing with the rest of the Anne series. The problem is, Anne's House of Dreams is a domestic melodrama and by Anne of Ingleside she has a passel of kids.

So instead he turned to the last three books in the series. Except the last three books are specifically about Anne's children.

I suspect as well that Megan Follows was already attached to the project. So Sullivan ended up with a mixed bag of story ideas written for an ensemble of younger characters, now played by a single person whose own character was by then completely out of sync with the original timeline.

The result, Kate points out, is a narrative mess, a scatterbrained script that jumps from one story idea to the next without paying off any of them, in the process turning Anne into

a sort of clean-living femme fatale. This week, she could end up with a German fighter pilot! Next week: the pool boy! A bucolic female James Bond.

Well, at least that means my idea hasn't been tried yet! There is more than enough good material in books four, five and six (Anne of Windy Poplars, Anne's House of Dreams, Anne of Ingleside) to create a contemporary television series. Hey, everybody's doing it with Sherlock Holmes.

I'm thinking of a lighthearted family melodrama about a GP and his wife returning to Prince Edward Island, where he sets up a family practice and she's an elementary school principal. Like the quirky Hampshire episodes in As Time Goes By, only featuring PEI as a major supporting character.

I can already imagine her kids suffering the twin tragedies of 1) ending up in a tourist trap in the middle of freaking nowhere (after living in, say, Toronto); 2) our mom's the principal! Aargh! And if you wanted to break a little fourth wall, 3) tourists can't stop observing that Anne look like, well, Anne.

Considering how popular Anne of Green Gables is in Japan, they could probably sign up NHK and the PEI Tourist Board as co-producers from the start.

Labels: anne, books, nhk, television reviews, thinking about writing

December 16, 2009

Ghibli's "The Borrowers"

The setting is the Tokyo suburb of Koganei. This shouldn't affect the essence of the book. Quite to the contrary, the story demands exactly the kind of charm and whimsy that Miyazaki brought to My Neighbor Totoro (wrote and directed) and Whisper of the Heart (wrote and produced).

And one of Miyazaki's first projects was an adaptation of Anne of Green Gables.

Labels: anime, anne, miyazaki, studio ghibli

August 25, 2009

Literary vacations

Prince Edward Island is a major holiday destination for Japanese fans of Anne of Green Gables. As a general rule, I would say that there must be some historic--other than pop literary--or aesthetic value to the place. So, while Sandy doesn't qualify, plenty of other tourist traps in Utah do.

But if you want to test the waters first without going there, try Google Maps. Type in the address or the general location. The satellite resolution available for places like Stratford-Upon-Avon is amazing. And you can even walk around Temple Square using Street View.

I'm writing a sequel of sorts to Path of Dreams. Part of it takes place at Mt. Koya. Although I spent a touristy day there when I was living in Osaka, Google Maps is an extremely useful tool for reminding myself where everything is. The bird's eye view alone kindles surprising feelings of nostalgia.

Being on the subject of (Mormon) vampires, Justine also links to her (favorable) review of Angel Falling Softly.

Labels: angel falling softly, anne, books, google maps, japan, lds, path of dreams, photo tour, twilight

January 05, 2009

A lily by any other name

My first sale as a writer was an autobiographical story to Cricket Magazine. In the published version, the editor changed the main character to a girl. I've favored female protagonists ever since. The New Era managing editor Richard Romney once said that I wrote female characters better than Jack Weyland. I still consider that one of the nicest compliments I've ever gotten.

Just to clarify, yaoi is a romance genre featuring guys falling for other guys. Yuri (meaning "lily") is a romance genre about girls falling for other girls. At first glance, the two would seem a complementary pair. Both are written (mostly) by women for (mostly) women. Just as yaoi is not seriously categorized as "gay" literature, yuri is not a synonym "lesbian" literature.

Furthermore, I've come to consider yaoi, if anything, as a rather strange "old school" extension of the Harlequin romance. Yaoi provides a curious solution to a knotty problem with the standard romance formula. Namely (and this is largely my sister's insight), that yaoi is a way of exploiting unequal power dynamics in romantic relationships while avoiding the taint of misogyny.

The "traditional" historical romance centers social and physical power in an alpha male--the pirate or prince or highwayman. The woman counters the total domination by the male with her sexuality and "feminine wiles." Following the customary evolutionary roles, the man ultimately "captures" the woman, and the woman in turn "tames" the man.

Translated to a contemporary context, though, this formula crashes into the wall of political correctness. The typical dodge is to give the alpha male a high-testosterone occupation or a much higher socioeconomic status than the woman (Michael Douglas in The American President, Tom Hanks as a corporate exec in You've Got Mail, Edward as, well, Edward in Twilight).

In a "chic lit" classic like Bridget Jones's Diary, Bridget is involved in relationships way above her social and economic class. And making women as sexually promiscuous as men, as in the hopelessly dreary Sex and the City, ultimately plays right back into the predatory male game plan, the old formulas rather transparently repackaged.

But if the relationship involves only men (quoting Kate),

then nobody has to excuse the blatant use of power. So teenage girls, who may feel rather powerless (since they have just seen their male counterparts gain weight, muscle and height that they don't have), may be drawn to material where real issues of power are played out without excuse or without the pretense that power isn't real, there and in your face.

The exaggerated and often S/M power differentials in yaoi essentially mirror Rhett Butler sweeping Scarlett off her feet and hauling her up to the bedroom, her protestations notwithstanding. It's retro Harlequin that conforms to every Freudian stereotype in the book.

Yuri, in contrast, tends to favor stories in which conflict arises from character largely outside men-are-from-Mars, testosterone-driven power struggles, and thus oddly mirrors classic action flick "buddy" pairings. In any case, class and power can't be entirely expunged from the narrative. There must be an aggressive member in the dyad or nothing would happen.

But while yaoi and genre romances tend toward idealistic or artificial narrative constructs (not that there's anything wrong with that--the same goes for guy entertainment), yuri (which, to be sure, hits porn at one extreme and lesbian literature at the other) remains largely rooted in how real people--specifically women--actually relate to each other in the real world.

As Erica Friedman puts it, yuri features "intense emotional connections between women" that can't necessarily be classified as love, but involve a "seriously intense bond that could easily become something more." Hence, to generalize, "mainstream" yuri can be said to revolve mainly around the evolution and devolution of friendships.

Many of the bittersweet, superbly-written short stories in Kawaii Anata ("Adorable You") by Hiyori Otsu, to take one exemplary example, could have run in the The New Era with very little tweaking. (The one place the short story is alive and well and widely-read by teenagers is Japanese manga.)

Similar yuri elements can be found throughout the Y/A canon. The kind of relationship Anne and Diane enjoy in Anne of Green Gables is a mainstay of yuri fiction. In her short story collection, Kuchibiru, Tameiki, Sakura-iro ("Her Lips, a Sigh, and the Color Pink"), Milk Morinaga has a character introduce herself as "I'm Diane to your Anne."

The core material from Anne of Green Gables, Anne of Avonlea, and Anne of Windy Poplars fits squarely into the yuri genre. Interestingly, these are the three novels that Kevin Sullivan tapped for his two miniseries, leaving out most of the formulaic (hetero) romance material from Anne of the Island.

Other examples includes Harriet and Beth Ellen from Harriet the Spy and The Long Secret (which I've always considered the better book) by Louise Fitzhugh. And at the other end of the genre scale, Lynne Ewing's Buffyesque Daughters of the Moon series.

Evolutionary psychology provides a useful tool for analysis here. Unless placed in a competitive context or placed outside behavioral norms (the nerds in any John Hughes flick) or given special attributes (every sports and superhero fantasy from Star Wars to Harry Potter to Spider-Man), normal boys are not that interesting. Unformed clay.

This is apparent in the NHK kid's show Whiz Kids. Imagine if the old PBS series Electric Company was produced by the Dr. Who people. The anime series Kodocha is based on shows like this, a bunch of preternaturally smart kids doing what a bunch of preternaturally smart kids would do with a television studio at their disposal.

Aside from the handful of adults who help "anchor" the show, the age cutoff for the cast is around twelve or thirteen. And reflecting a phenomenon that every geeky teenage boy is painfully aware of, while many of the girls can be categorized as "young women," the boys are still Bart Simpson. Even the preternaturally smart ones are candles competing with tungsten arc lamps.

Manga publishers and anime producers have long known that they can exploit this painful differential with some gratuitous nudity or by dropping yuri-ish hints into otherwise "guy" material--the vicarious thrill of imagining girls getting hot and heavy with each other being preferable to watching the kind of girl you'll never have doing the same thing with the BMOC.

The necessity of this spark remains when the hinting and nudging is taken away. In The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya, Kyon is a blank slate until Haruhi bounds into his life. In Ah! My Goddess, Keiichi is immobility incarnate, even after Belldandy shows up. In Sing Yesterday by Kei Toume, Rikuo hasn't gotten to first base with Shinako or Haru after six volumes.

Alas, the brilliant Ranma 1/2 begins to grate when you realize that, male or female, he's never going to grow up.

To compare, Akiko Morishima's collection of yuri short stories, Rakuen no Joken ("Conditions of Paradise") isn't chock full o' plot either. But Morishima's wonderfully-drawn stories and realistically-aged characters do depict lives moving forward, which is enormously more satisfying.

The odd shounen exception proving the rule are manga like the Kimikisu series, based on dating sims. Because the whole point of a dating sim is to challenge the player to round the bases, the story has to go somewhere with a refreshing alacrity. Kimikisu boasts little else in terms of plot--getting to first base alone is a challenging-enough goal. But at least they get there!

Now, I do understand characters like Ranma, Rikuo, Kyon and Keiichi. The old evolutionary instincts grinding away in the background. It's hard for guys to move off the dime without the sense that they're accomplishing something concrete, conquering new lands, rising in a hierarchy. As in every Bond film, consummating the relationships celebrates the end of the quest. Game over.

Hence the constant keeping of things at arm's length. In contrast, shoujo and yuri protagonists are more likely to get up close and personal, pushing the story along romantically and physically. Because that's when things start getting interesting.

Nor, I find, am I alone in this assessment, as yuri manga-ka like Milk Morinaga and Takako Shimura write for magazines whose primary market is men.

To be even-handed, an equally deadly plot device on the shoujo side is the love triangle. Again, evolutionary psychology explains why geeky guys in particular loath the conceit: when two males compete for a female, somebody's going to get hurt, and probably the guy wearing glasses. For the Mary Sue, the duplication of attention is great for her self-esteem. Hell for everybody else's.

In Anne of the Island, L.M. Montgomery creates two interlocking love triangles, which means that everybody suffers. Kevin Sullivan's adaptation skips quickly through the love triangle business (using an either/or formula which denies the hedged bet), making the movie better than the book (though as I point out here, it slights Anne's educational accomplishments).

Granted, shounen manga and anime writers invented the male version of this, known as harem. And it's just as annoying, especially lacking any hope (in the non-porn genres) of consummation.

To be sure, Robert McKee argues that we shouldn't expect fiction to mirror real life, but for fiction to capture something that is like real life, a distinction that confuses too many artists. In the excruciatingly gorgeous 5 Centimeters Per Second, Makoto Shinkai vividly captures (in the very last frame) a very real moment of self-realization. Been there, done that. I can identify.

And that's the problem. Plot is a necessary condition, not a sufficient condition. We ultimate invest in the character of the characters. And at the end of 5 Centimeters Per Second, we realize we've invested an hour of our time in a character who doesn't have any. Real? Like, man, I'm grokking it totally. But entertaining? Not beyond the dazzling cinematography.

In Video Girl Ai, Youta spends the entire series summoning up the courage to admit that he loves, well, Ai or Moemi, he's not quite sure. But at least in the end he's willing to pay a literal ferryman and literally walk across broken glass to seal his decision. Just punishment for all the angsty dithering he's put us through.

If nothing much is going to happen--essentially the most real thing about real life for most of us--then character must become the summum bonum of the story, without placing the protagonist's travails infinitely beyond the grasp of the reader. For me, yuri's consistent ability to accomplish this makes it perhaps the most "realistic" of niches in the otherwise unreal romance genre.

Labels: anime, anne, criticism, japan, manga, nhk, publishing, shinkai, yaoi, yuri

December 01, 2008

Anne Shirley explains "Twilight"

ANNE: Oh, it seems so funny and horrible to think of Diana marrying Fred. Doesn't it?

MARILLA: What is so horrible about it?

ANNE: Well he certainly isn't the wild, dashing young man Diana used to want to marry. Fred is extremely good.

MARILLA: That is exactly what he should be. Would you want to marry a wicked man?

ANNE: Well, I wouldn't marry anyone who was really wicked, but I think I'd like it if he could be wicked and wouldn't. [Montgomery places the above line here: "Now, Fred is hopelessly good."]

MARILLA: You'll have more sense someday, I hope.

Yep, nothing poisons a romantic fantasy faster than the prospect of a boyfriend who's hopelessly good.

Sullivan then illustrates this axiom by mostly inventing the character of Morgan Harris (Frank Converse), as a wealthy, dashing scoundrel who could be wicked but isn't. Of course, in the end Anne chooses Gilbert, the "boy next door." Gilbert, though, is in medical school, and they postpone the wedding until he earns his M.D.

The bulk of the material in Sullivan's second adaptation comes from Anne of Windy Poplars, the fourth book in the series. In L.M. Montgomery's version, Anne has by then earned her teacher's certificate and her B.A., and is the principal of the school. The sour, cynical Katherine Brooke is one of her teachers.

Sullivan's condensation created a timeline that couldn't account for the ten years that actually elapse between books one and four. So he makes Katherine Brooke the principal and Anne the teacher. Lost is the point that back in 1936, Montgomery quite progressively imagined a marriage of equals between her two protagonists.

But to give credit where it's due, I think Sullivan improves on the overall structure and especially the ending of Anne of the Island (in my opinion, the weakest volume in the series). Accepting Gilbert's proposal (second time around in both cases), Anne says:

I went looking for my ideals outside of myself. I discovered it's not what the world holds for you, it's what you bring to it. The dreams dearest to my heart are right here.

Anne doesn't wear her spunky personality like so much jewelry, but changes and improves herself, and thus her world. L.M. Montgomery created a character as revolutionary then as she is now, which may explain why Anne of Green Gables remains one of the best-selling books of all time (over 50 million copies sold).

Labels: anne, criticism, deep thoughts, twilight